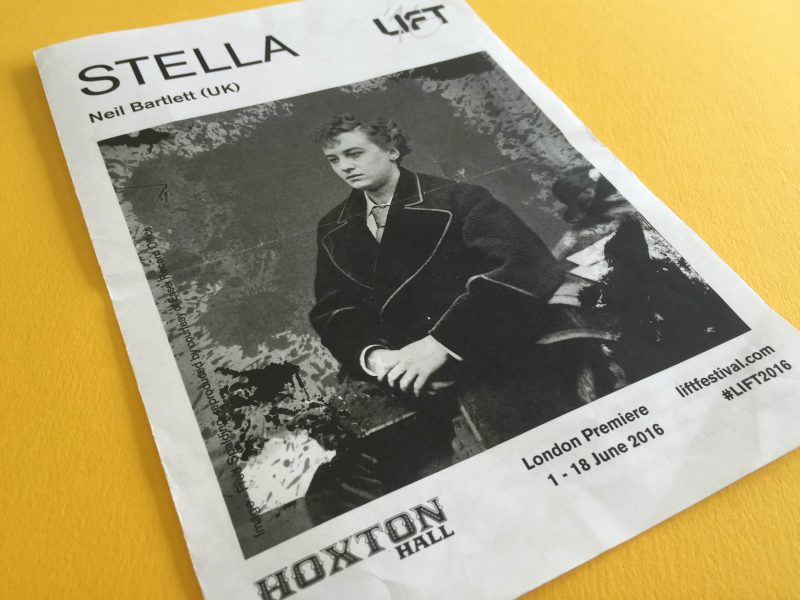

October’s Cog Night was the revival of Mark Ravenhill’s shocking debut. Would this production at Lyric Hammersmith still have the power to offend? Matt gives us his opinions.

Shopping and F*cking at Lyric

Mark Ravenhill’s debut play was brought to the stage by Out of Joint, and first performed in 1996, upstairs at Royal Court. Their sweary advertising caused quite a fuss when it transferred to the West End, and the play’s bleak portrayal of ’90s society was met with equal measure of disgust and delight. ‘It may be the most important play of the decade.’ The Stage.

Part of the ‘in-yer-face’ British theatre scene, the play took mid-nineties lad-culture and the acid-house comedown, and reflected it back on the society that created it.

It may be the most important play of the decade.

Famously the characters’ names are taken from the bands East 17 and Take That (and their collaborator Lulu). Twenty years have passed and much has changed, not least in the life of Gary Barlow and Robbie Williams. I was too young to see that original production but I know that Robbie has since turned to UFO spotting and Gary is as revered for his efficient accounting as he is for song writing. Would the play have drifted into such middle-age? Would it still be shocking? Would the references still feel relevant? I was keen to find out.

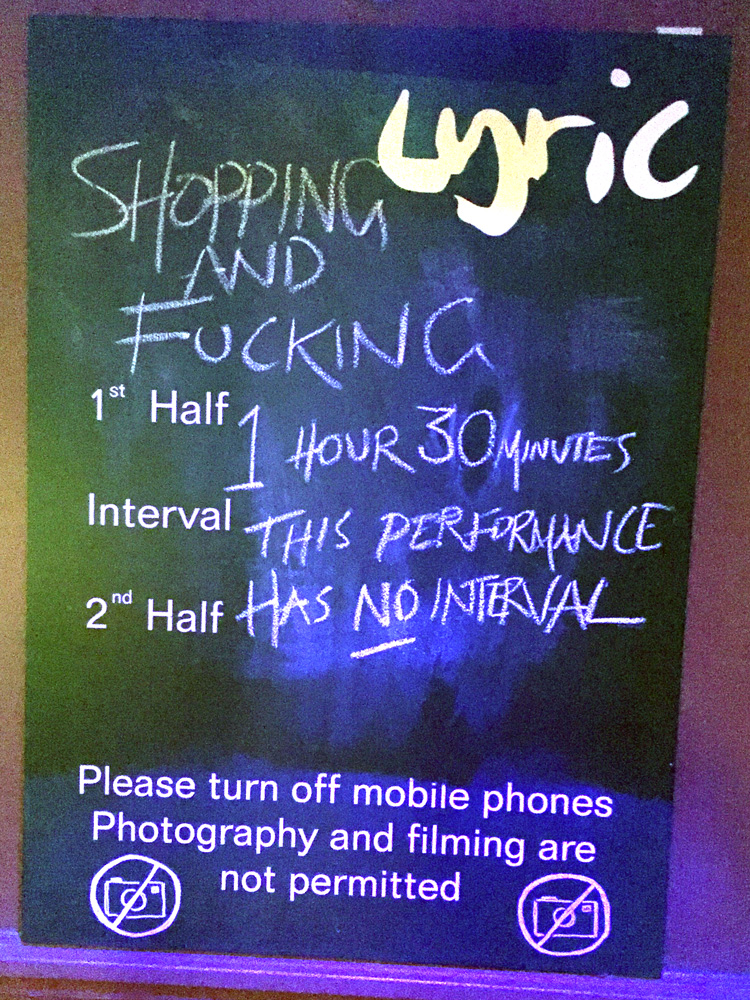

The Lyric revelled in the play’s offensive reputation, but the ‘F’ word is still powerful enough that they starred it out on posters (and we’ve starred it in the title of this post, for fear of offending the Google arbiters). Staff in the bar encouraged us to buy merchandise as they wore ‘Shopping and Fucking’ t-shirts with swearing taped over.

As we approached the theatre entrance, signs warned of a long list of content you may find disagreeable. It looked like it was going to be a fun night.

As we sat waiting for the play to begin I tried to avoid eye contact with staff who were eagerly touting more tat, walking through the aisles, climbing into the balcony. They were very engaged in their delivery, a little too engaged to be normal ushers. Then I clocked it, these were the actors, working the captive audience, setting the scene.

The whole auditorium had been converted into steeply raked seating, set-up like a TV studio. The stage was decorated like a gameshow with lurid promotional signs, green-screen backdrops and flashing video screens of bold type – Buy, Buy, Buy.

Straight from the opening we learn the key message – everything is for sale. Actor Sam Spruell stepped out of his usher’s role and up onto the stage, staying this side of the fourth wall. Addressing the audience, he offered a pair of premium on-stage seats for a fiver – who wants ’em? Apparently lots of people as there was quite some competition to hand over the money and take the seats.

Get the money first … The getting is cruel, is hard, but the having is civilisation.

Sam’s tone is loud and genial. It feels like a light entertainment show but the jokes and winks to the crowd are already hinting at a more adult nature. He needs a coin to start the show – who has a coin? He takes a pound from a man in the front row, puts it in a slot in a box, ker-ching, Sam turns into his character, Mark, and we’re off.

As the play’s housemates first gather on the stage they casually strip to their underwear. Perhaps more for the shock than narrative purposes. Oversized price tags hang from every garment.

The story begins with Mark passing through rehab in an attempt to separate from his serial addictions. Starting afresh he avoids the complications of emotional attachment by turning each encounter into a transaction.

Meanwhile his housemates (who we hear he picked up in a club some time ago) get tangled up in a world of seedy, on-screen selling, drug dealing and internet sex. They are alienated without direction or hope.

A promotional image from the Lyric’s website.

Emotions always kept at a distance, sincerity is expressed through unexpected karaoke renditions of pop songs – saccharin lyrics pushed past believability. Morals are handed out by a gangster come preacher-like figure leader, Brian (payed by Ashley McGuire), drawing references from The Lion King and misquoting the bible. “Get the money first … The getting is cruel, is hard, but the having is civilisation. “

The writing is sharp and witty. Knowing and satirical. The production plays with ’90s cultural references – jumping into The Shamen’s Ebeneezer Goode dance breaks.

A promotional image from the Lyric’s website.

At the beginning of the play, all is shown as light and without consequence. As time turns, things fall apart. Prostitution, abuse, and rape is treated with such normality that it appears dehumanised. The characters need to desensitise themselves just to cope. This makes the play uncomfortable to watch. You want to leave but you can’t draw your eyes away – like desperately browsing through tv channels numbered higher than 50 when you know you shouldn’t go past 4 (at least I’m told that was what TV was like in the mid-’90s).