For August’s Cog Night we were at the Hayward for a fantastical journey though the mystical minds of 11 contemporary artists from the African diaspora. Michael gives his thoughts.

In the Black Fantastic

I’m always a bit torn when going to an exhibition. Should I read up on it first or should I let the art speak for itself?

I made the wrong choice this time because there was very little interpretation in the space; I’d have got a lot more out of this exhibition if I’d done a bit of pre-show reading, or downloaded the app.

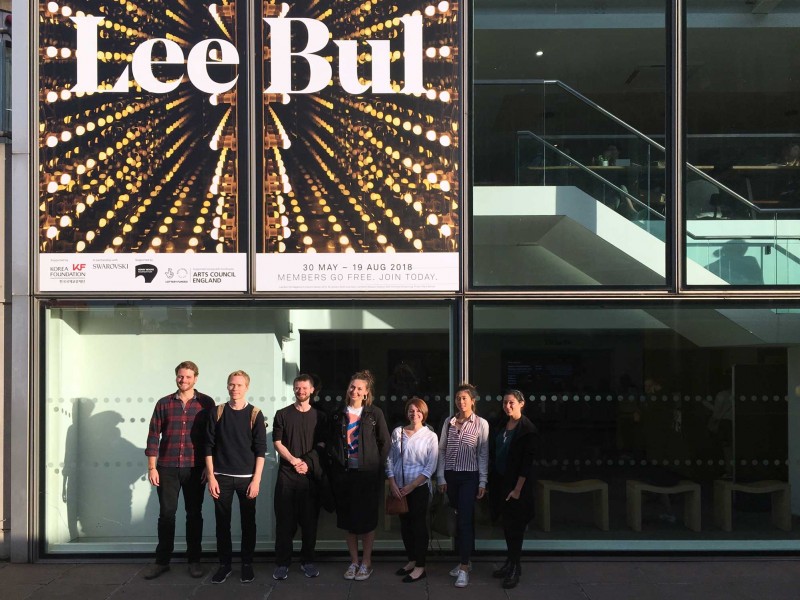

The Cog team, ready to be In the Black Fantastic.

What I think I took away from it was that each artist represents interpretations of the experience of people of colour, through the lens of myth, symbolism, story-telling and realigned imagined futures, but all rooted in the horrors of the slavery, the legacy of racism and the daily realities of the African diaspora. Maybe.

One thing I am sure of is that the show was great and it has prompted me to read-up, watch interviews and listen to podcasts to learn more about the artists and the worlds they conjured. That’s got to be a good thing.

The Hayward Gallery space is divided into rooms or sections; each one dedicated to an individual artist.

I won’t attempt to describe each but I’m keen to note some personal highlights as it’ll help me remember the experience of being there.

Entering the space you are in the American artist, Nick Cave’s room. I’d not heard of this Nick Cave before and the work was a revelation.

One of Nick Cave’s Soundsuits

The artist started creating Soundsuits in response to the public beating of Rodney King by police, the incident was captured on camera (which was unusual at the time) and I remember watching news of the rioting that followed, and images Los Angeles on fire.

Cave’s response was to create these shimmering, peacocking outfits that camouflage the wearer’s shape, creating a second skin that hides gender, race, and class, obliging audiences to watch without prejudice. He’s made more than 500 and there were a few beautiful example dotted around the room.

Nick Cave's 'Chain Reaction'

Nick Cave's 'Chain Reaction'

But it was a very different work that dominated the space and most captured my attention. Chain Reaction cuts the huge ground floor gallery in two, a fence of linked hands stretch from floor to ceiling.

The title might suggests chains of bondage, but there’s a fragility rather than strength in these casts of Cave’s own hands. Each one gripping to another by its finger tips. It’s a static work but there’s implied movement and clear rhythm. The more you stare, the more desperate each grip becomes: hands pull people up, and are on the edge of losing their grip; each strand gets progressively weaker as more people try to climb.

There are even a few scattered on the floor; up close they look like the fallen, from a distance like the next links to be pulled aloft.

Wangechi Mutu's sculpture and collage work

Wangechi Mutu's sculpture and collage work

Wangechi Mutu’s 'The End of Eating Everything'

Wangechi Mutu’s 'The End of Eating Everything'

Heading up the ramp, Kenyan born American Wangechi Mutu works in a wide range of media. The video art was fun and the collage work was engaging but it was the sculpture that kept drawing me back. Her figurative works use Kenyan traditions, shapes (and animals) from nature, jutting limbs and headdresses of hair. Against the mud-red walls they felt like 3-D versions of Francis Bacon’s most disturbing works.

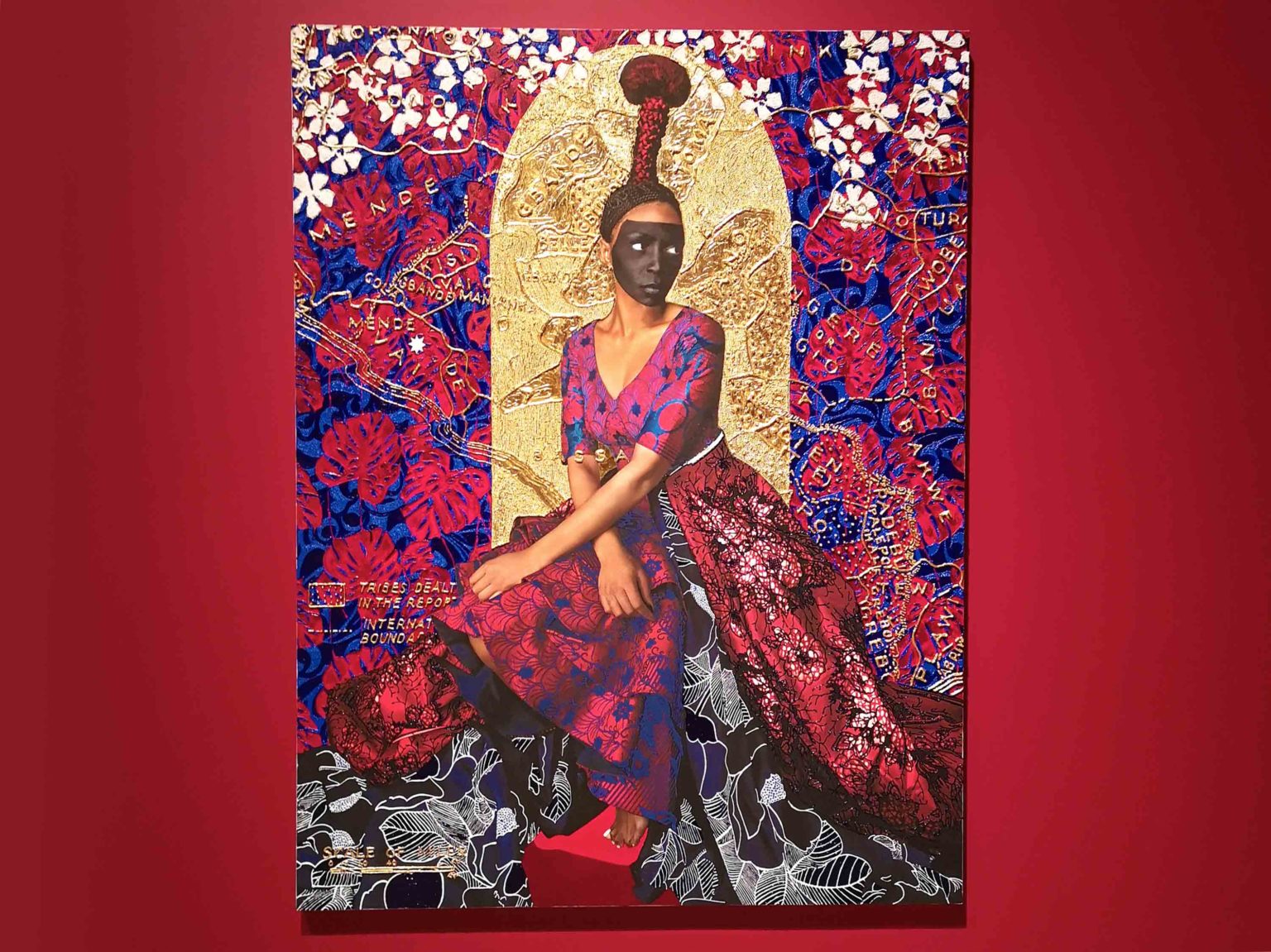

Lina Iris Viktor's 'Eleventh'

Lina Iris Viktor's 'Eleventh'

The work of British-Liberian artists, Lina Iris Viktor is immediately arresting. In her series ’A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred’ she places herself (I guess) in the centre of deep, lush formal portraits, framed in the symbolism of gold and rich reds and purple. She become an historic queen or mythical goddess, each time her face is enhanced with makeup much darker than her own skin.

The backgrounds are filled with symbolism and maps. Viktor is fascinated by the boundaries that maps impose, the colonisation and division of native people and tribal lands.

In this 2018 work, Eleventh, an American Colonization Society map shows areas in West Africa and outlines (in gold) plans to create Liberia. The established population was ignored, a new nation of freed slaves imposed on top of that existing geographic and cultural landscape.

Kara Walker's hand-cut projected silhouettes

Kara Walker's hand-cut projected silhouettes

Kara Walker’s room featured beautifully detailed, hand-cut, animated silhouettes. The imagery was gorgeous but the stories being told were harrowing – reenacting white supremacist atrocities, visualising racist novels and acting out the Trumpian symbolism of the alt right.

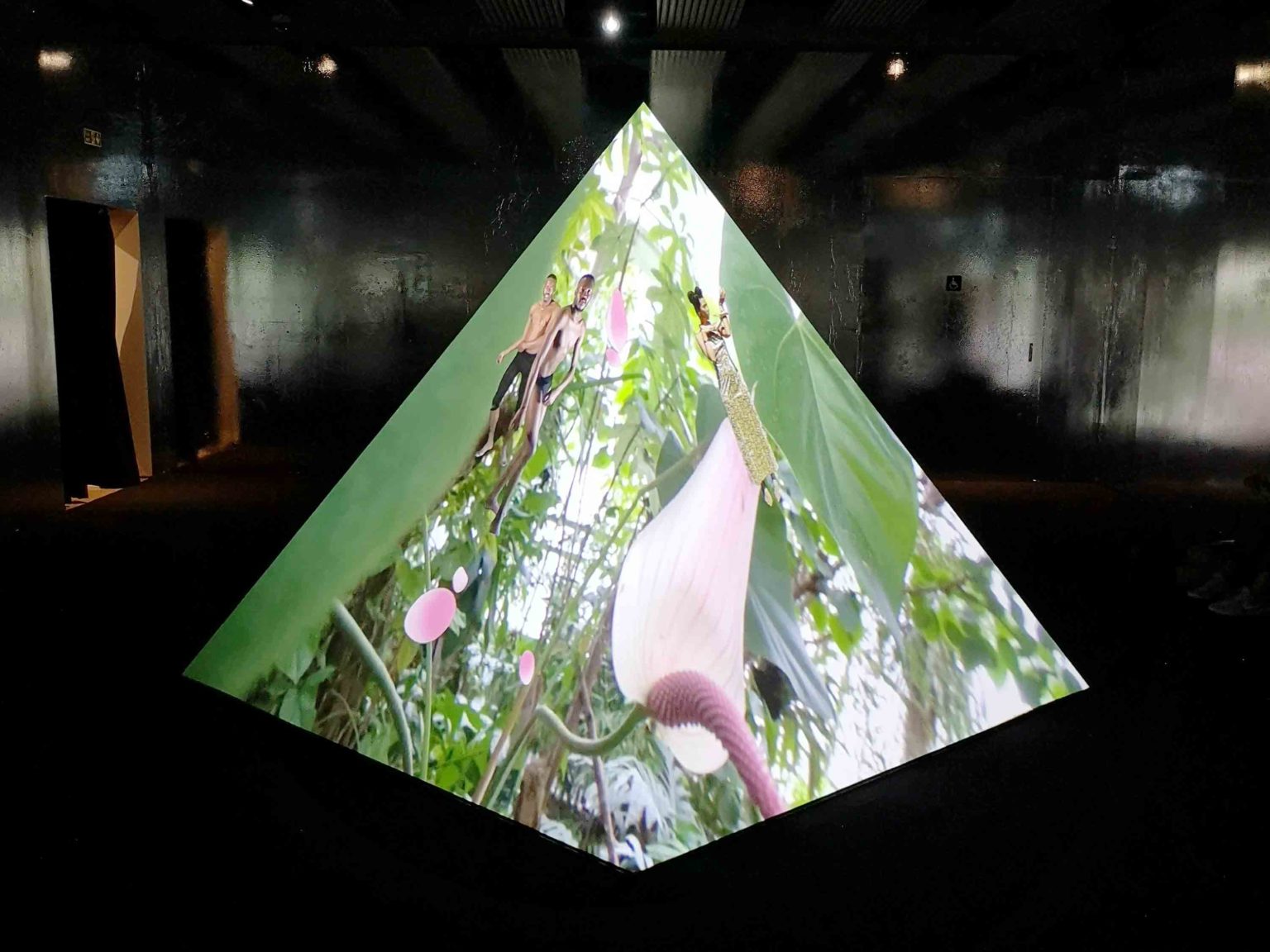

Tabita Rezaire's mystical pyramid

Tabita Rezaire's mystical pyramid

Part of Cauleen Smith's table-top collection of objects

Part of Cauleen Smith's table-top collection of objects

I wasn’t as excited about every room. I’m a sucker for a crow but Cauleen Smith’s collection of bric-a-brac, some projected on the wall, left me confused.

And I think I can skip over the room filled with projections onto a pyramid and talk of mega-dimensional female energy. Or maybe I need to read up more to understand that.

One of the characters from: Survivors on Horseback in a dystopian, burnt-out landscape, heading to the future

One of the characters from: Survivors on Horseback in a dystopian, burnt-out landscape, heading to the future

The final room to really capture my imagination was filled by Hew Locke. His recent procession work at Tate Britain had dominated my Instagram timeline.

This room was less expansive than that installation but no less impressive. Around the walls you could find Hew’s image in large scale photographs, camouflaged as a sinister spectre hidden in coats of arms and the symbolism of dominance.

But it was another procession themed work that took my breath away. In ‘Survivors on Horseback in a dystopian, burnt-out landscape, heading to the future’, magnificent characters sit atop their mounts. Their clothing, baggage and horses are covered in symbols of revolution, victory, overthrown oppression and colonialism. They strike stunning silhouettes like statues to the conquerors of mythical empires. But up close they are small, quarter sized, quixotic characters, alone and fragile, heading forward but leading no-one.

When I was young (and he was the same age) Ekow Eshun used to write in the newly published men’s magazine, Arena. I could tell they were clever reviews and articles but I found the writing impenetrable; his academic dissections intimidated me. I was embarrassed by my lack of knowledge and grasp of the topics and often gave up a couple of paragraphs in.

Three decades later Eshun is a global figure, curator, writer, chair of the Fourth Plinth commission and ex-director of the ICA. He used his influence and connections to curate this wonderful exhibition (and keep the idea alive through the pandemic). Maybe I need to buy the book and have another go at reading his essays.

Illustration by Taja Bright for our Cultural Calendar.