This is the first of an ambitious programme for the RSC. Under Artistic Director, Gregory Doran, the company will stage each of Shakespeare’s plays, just once, between the anniversaries of Shakespeare’s birth (450 years, this year) and his death (400 years in 2016).

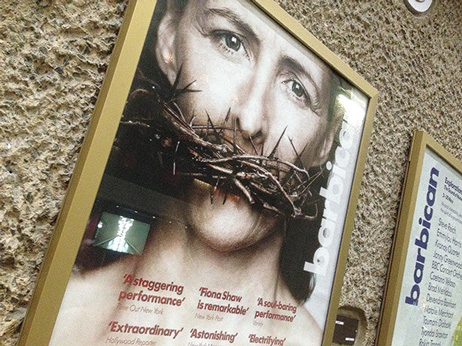

RSC’s Richard II at Barbican Theatre

Richard II is a bold choice to start the season, it’s less frequently performed than other Shakespeare plays, and Richard is an unlikeable complex character without the powerful masculinity of other tragic leads.

I was nervous about going to see it as I had so little grasp of its historic context. In fact, I had to look it up on Wikipedia before I went; that’s embarrassing, isn’t it? If nothing else, the RSC production of Richard II has resolved me to learn more about English history.

This loaded metaphor is played perfectly as though this crown, this power could go off at any moment, neither man sure how he will emerge from the encounter.

David Tennant is perfect casting for the title role. He’s credible amongst his peers, has the Doctor Who celebrity to draw in audiences, and has the pedigree (of his recent title role in RSC’s Hamlet) to impress even cynical theatre audiences. He’s also brilliantly subtle and mercurial in the role.

Doran’s production begins as most people are taking their seats in the Barbican Theatre. A coffin sits, centre-stage, the Duchess of Gloucester weeps across it as choristers chant from a gallery. This simple directorial device places us in history and sets the context for the entire play; it also builds the atmosphere by silencing the arriving audience into immediate reverential hush.

The Barbican Theatre also plays its role. I love the drama of the space and the moment when the lights go down and the doors (at the end of each row) are released and swing closed to envelope you into the auditorium.

Through projection and rigging, we are transported to historic scenes of stone columns, vaulted ceilings and elevated thrones. The Royal Court maintains the rights of divine attribution, but Britain is beginning to question the absolute power of their capricious King.

Tennant’s brilliance is his ability to make an effete, physically frail, child-like character into such a menacing presence.

At first, Richard seems bored by his role, weighed down by the burden of ruling his squabbling court. He sees himself as just and even-handed but everyone around him knows that their fate hangs in the balance of his petulance.

Presiding over a dispute between his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, and nobleman Thomas Mowbray, Tennant’s Richard tries to get the men to forgive each other but quickly tires of this and agrees to their duel. His subsequent halting of that duel and banishment of its protagonists proves to be Richard’s tragic undoing.

When Bolingbroke returns with an army, and gathering the support of the disenfranchised nobility, he offers Richard his loyalty in return for what was justly his (the lands and status taken at the death of his father, by Richard, to fund war in Ireland). Richard is unable to accept a bargain with his cousin who should be bowing to his God-given title.

Tennant’s Richard knows that he is finished but will not go easily. He toys with the crown like a gun in a filmic hostage negotiation, offering it out, snatching it back, grasping it between he and Bolingbroke. This loaded metaphor is played perfectly as though this crown, this power could go off at any moment, neither man sure how he will emerge from the encounter.

As I’d read on Wikipedia, Richard does relinquish the crown and Bolingbroke becomes Henry IV and so the title character of two more of Shakespeare’s plays comes to power. The RSC are staging Henry IV parts I and II, in Stratford, this year, I’ll be booking my tickets soon.