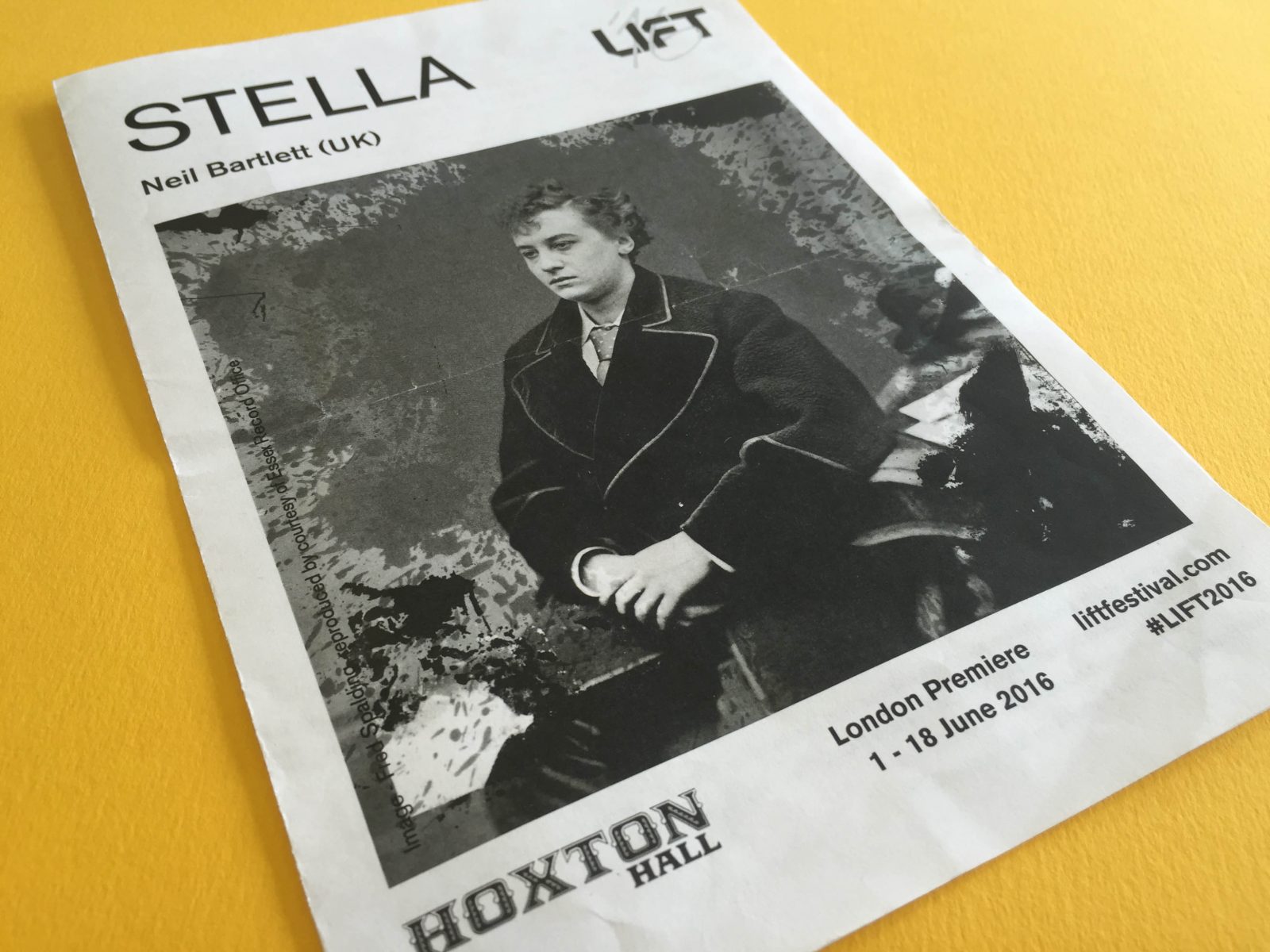

The ‘true’ story of infamous Victorian socialite, Ernest Boulton AKA Stella, is given an emotionally driven yet enigmatic treatment in Neil Bartlett’s new play. Melissa tells us what she thought.

Neil Bartlett’s Stella at LIFT Festival

For June’s Cog Night, we headed to Hoxton Hall for the LIFT (London International Festival of Theatre) presentation of Stella, a new play from Neil Bartlett. From the buzz of a sunny Hoxton evening there was an instant contrast stepping into the cool shadows and forgotten by time feel of the interior of Hoxton Hall, which has been newly refurbished, yet retains an air of history. In the low light we see on stage a solitary figure in a crumpled suit sat hunched, waiting. As the lights dimmed to black and the audience grew silent he continued to wait, and us with him – though for what was uncertain. His fragility palpable, his frame hollowed out, whatever is coming, we sense, will be terminal. And so the story begins to unfold as the recollections of one apparently near to death brings to life a previous self, a different self… Enter Stella, the vivacious and glamorous young woman, alone in her dressing room, also waiting, though she for her lover, and life is in full swing.

There is a detailed history included in the programme, written by Neil Bartlett, the playwright and director. We discover that this is about Ernest Boulton, an infamous Victorian socialite, and that Stella was perhaps the most successful of his many alter egos, a respectable young lady of London’s West End and the lover of the Tory MP and aristocrat Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton. They lived together briefly before the scandal of Stella’s arrest and trial in 1870 (although surprisingly, Boulton was not charged with sodomy). It’s a fascinating story – one that Bartlett has researched in detail. And yet the factual elements of the story barely make it onto the stage. Rather, the approach is a more poetic musing on memory, on identity, on the reflections, refractions, surfaces and depths of a self within a self, and the relationship between them. It seems the subjective experience of the character(s) is really what the play is trying to convey, relying heavily on prior knowledge to fill in the narrative blanks.

Ernest and Stella are invoked in a split-screen-like staging, as the two main actors, Richard Cant and Oscar Batterham (who are excellent) deliver stream of consciousness soliloquies that at times echo each other across the divides of age and gender. However, the relationship between the two is not immediately clear, and is further complicated by the mysterious and silent presence of a third actor, David Carr, who seems to be somewhere between a stage hand and a prop, who mainly watches silently from the background.

Themes of mirrors, reflections, of image and surface, individuality and multiplicity, of continuity and contrast are evoked throughout the play as part of the exploration of this historical character, yet are recognisable to a more modern sense of self, and also to current discussions and experiences of what gender might mean. And while this is clever and thought provoking there is a strong sense of considered literary devices at work here, which ends up detracting somewhat from the accessibility of the story. The deliberate ambiguity that is part of the intriguing dream-like quality of the play is both a help and a hindrance. However, the physical performances of the actors shine through, and it is the nuance and flair of movement and delivery that most vividly conveys the characters. Perhaps the restrained staging is a nod to the constrictions of Victorian society which the play’s namesake inhabited.

After the play, as we shuffled out of the theatre, blinking like moles in the still bright sunlight, I was struck by the sense of dissociation. We had certainly witnessed something, which was probably quite good, performed with notable skill and Interesting Content, but missing the mark of an experience easily enjoyable.