We all know we should use apostrophes correctly. But do we know how? Michael guides us through the rules and many exceptions.

The apostrophe. When and how to use it.

I have no recollection of anyone ever teaching me how to use apostrophes. Maybe I’ve blanked it out or maybe I was off sick that day. Or perhaps it’s one of those things you’re supposed to just know.

I have always found them confusing. I think other people must too so I thought it might be a useful topic to summarise somewhere. And, in the absence of anywhere else, I’m putting it here.

Part of the confusion is, I think, that some people get really cross about a particular use of apostrophes and their smart-arse certainty makes other people embarrassed at our own lack of knowledge.

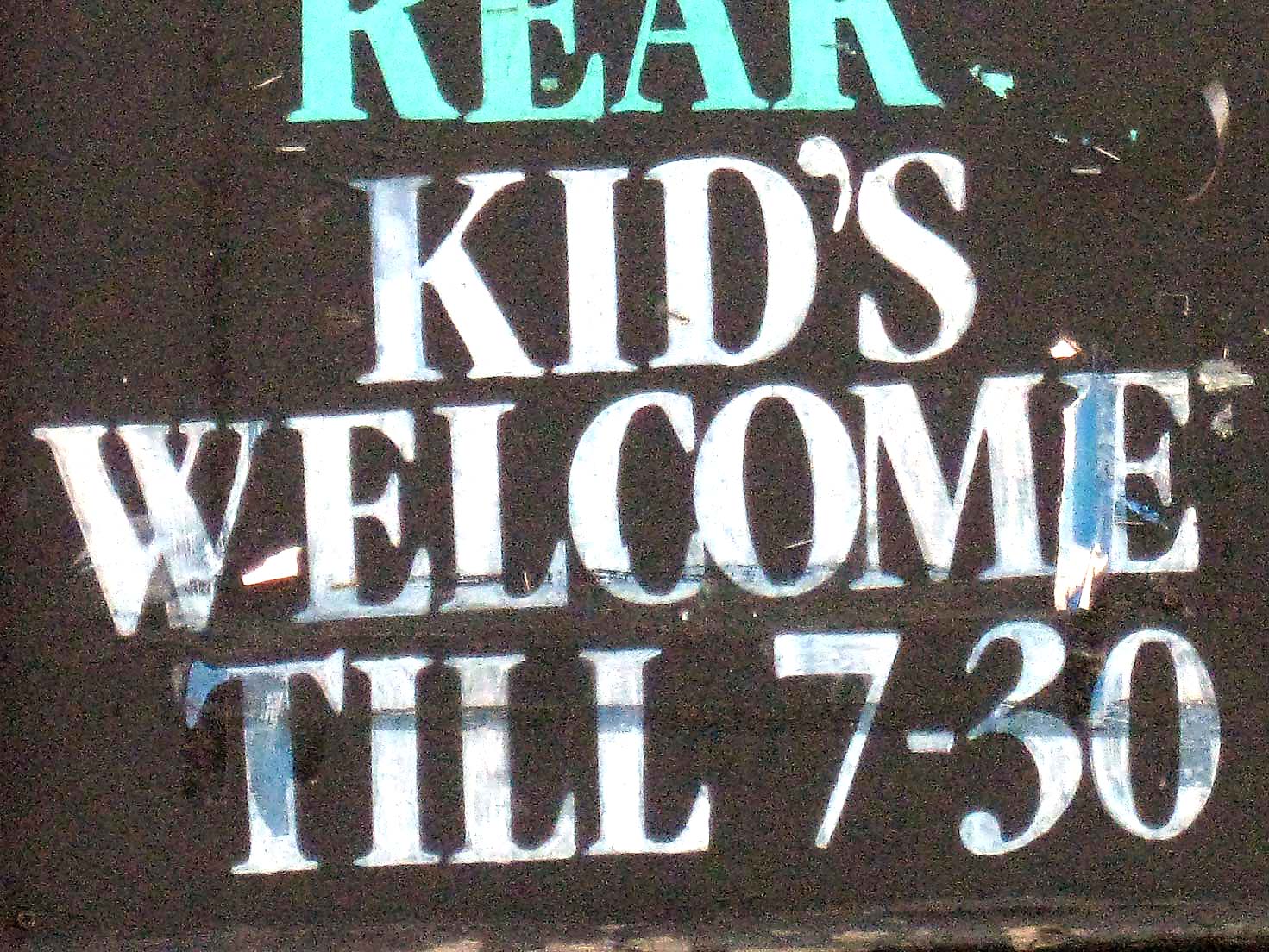

A car park sign, vandalised by the apostrophe police.

In our society we conflate knowledge with intelligence and that drives me potty. But that’s a topic for a different post.

Apostrophes exist to help us communicate more clearly. So, if your audience understands you perfectly without them, then dont worry.

But if we want to use apostrophes correctly, to convey meaning, then it can be useful to know the rules and many exceptions.

There are two main uses for apostrophes:

- To show where letters (or numbers) have been omitted

Dave likes Rock’n’Roll but can’t dance - To indicate ‘possession’

Dave’s skirt was printed with a ship’s anchor motif

And three less common uses:

- To indicate heritage in some names

Dave O’Kelly would never go in O’Neill’s bar - To express multiples of letters, symbols and some short words

Dave used many f’s; he should mind his p’s and q’s - To indicate quantity (including time)

Let’s give Dave an hour’s grace

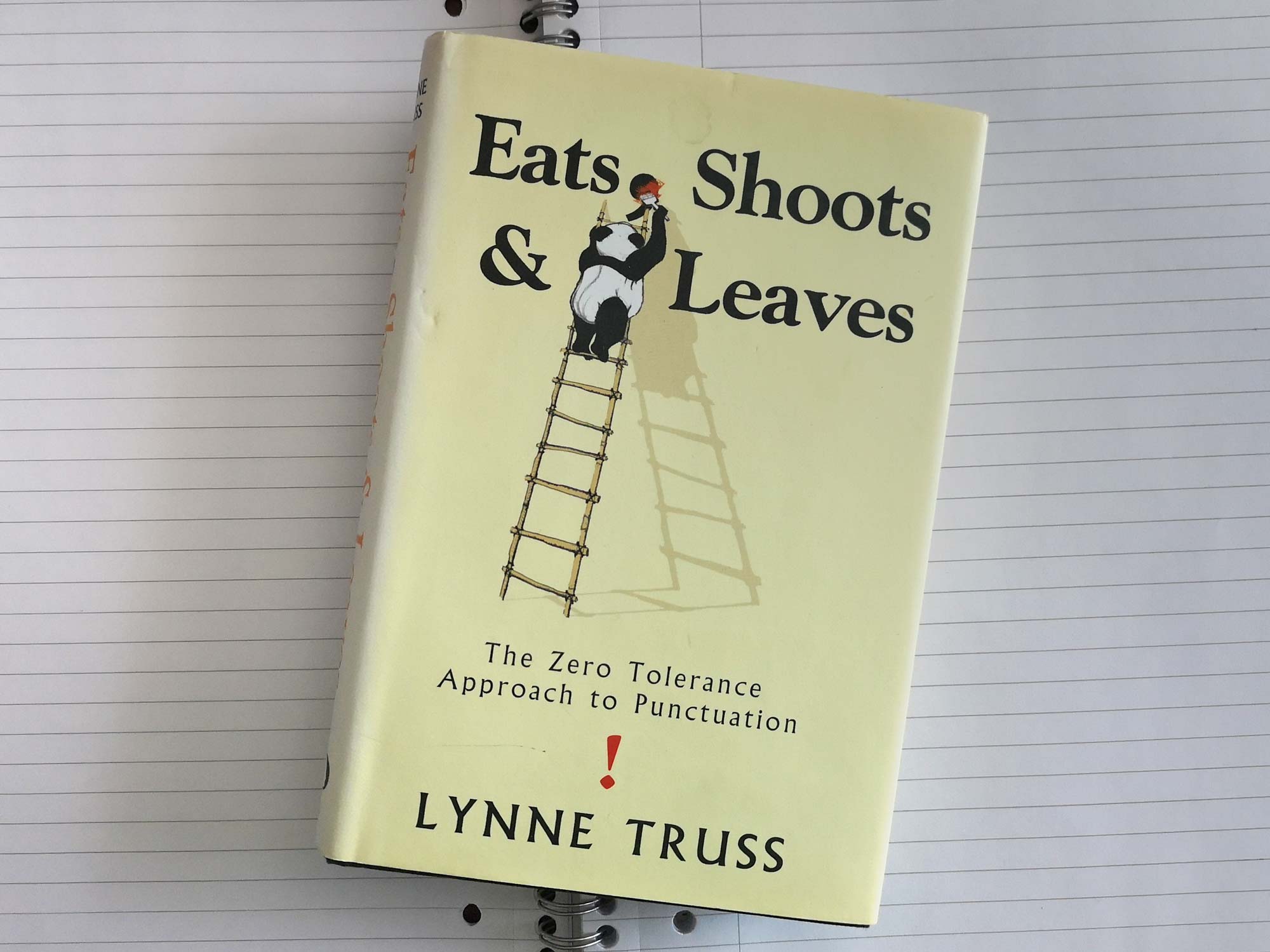

The cover of Lynne Truss’s (or Truss’) excellent book.

Let’s unpick those in turn…

1. To show where letters (or numbers) have been omitted

The writer, Lynne Truss, has published an excellent book about the principles of everyday English – Eats, Shoots & Leaves. It’s a brilliantly succinct and funny guide. Do get hold of a copy.

In it she says we should imagine that the apostrophe as a marker, like a tombstone, left where a letter has been dispatched.

The only ‘rule’ to follow is that they appear one at a time (and can represent single or multiple letters, or even whole words). So…

Four of the clock becomes 4 o’clock; should have becomes should’ve; I am becomes I’m. And… It is becomes it’s (and so does it has).

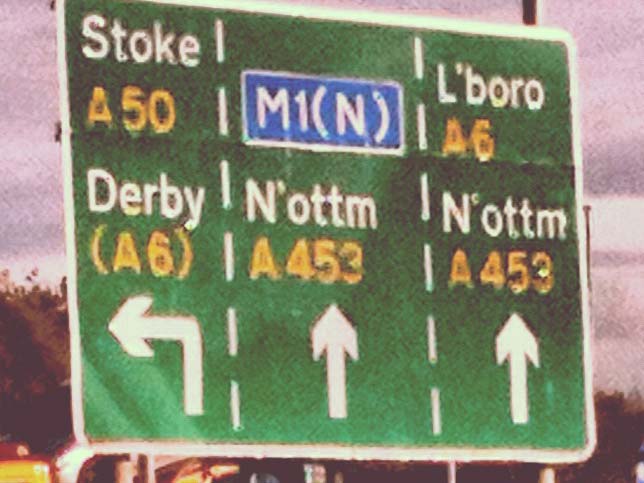

But they aren’t just shoved in at random as they seem to be in this road sign below. Nottingham might be abbreviated to Nott’m but never N’ottm.

A road sign with strange apostrophe use.

As language develops, and abbreviated words come into common use, the apostrophe is often dropped from use. So…

Perambulator is now pram (not p’ram’); refrigerator is fridge (not ’fridge).

The same principles apply to occasions when numbers are omitted from dates. So…

Michael was born in the summer of ’69 and Cog was founded in the ’90s.

The example that catches me out most often is the difference between you’re (to abbreviate you are) and your (to mean owned by you). I think it’s because possession is another common use of the apostrophe.

2. To indicate ‘possession’

I think this is the area that gets a lot of people hot under the collar because it seems simple but it quickly gets complicated, as this long explanation indicates…

Perhaps it’s the word ‘possession’ that confuses us. Some people latch onto it and take it too literally.

For instance: if I write about the headteacher’s school that makes some sense because the school may be run and therefore, I suppose, be possessed by the headteacher.

But it’s also correct to write about the child’s school. The child doesn’t own the school so in what way is it a possession?

It is useful try and swap the words around and see if they would make sense when we add other words to define ‘possession’: the child’s school could be rewritten as the ‘school of the child’ or ‘school attended by the child’.

So ‘possession’ is kind of the right word but only when used in quite a loose context.

By the same principle, something that is named after someone should also use an apostrophe… Miller’s Crossing, Satan’s Passage, The Queen’s Arms. They don’t ‘possess’ those things but they are ‘of’ them.

A pub in Deptford. The sign seems to be pointing out the fact that the birds do indeed ‘nest’.

It can get more complex when we talk about plural words.

If a plural doesn’t end in an ‘s’ then it follows the same principles of adding ‘apostrophe +s’. We might refer to a women’s refuge or a children’s playground. But most English plurals do end in an ‘s’.

If we follow the same principles and add ‘apostrophe +s’ then the words sound clumsy: they attended an all boys’s school feels strange (perhaps for multiple reasons).

So we drop the second ‘s’: the incident occurred in an all boys’ school.

And what about words that end in ‘s’ that aren’t plurals?

Of course only nouns can ‘possess’ things. Thankfully there are very few single nouns (that aren’t names) but do end in an ‘s’ (or an ‘s’ sound). But there are some: mathematics, billiards, police etc.

That all gets a bit messy. It’s not wrong to write about billiards’ rules… but it does feel awkward so instead we would probably say: we were discussing the rules of billiards.

And then there are ‘proper-nouns’ or names as we might more normally call them. And this throws up an extra point of contention.

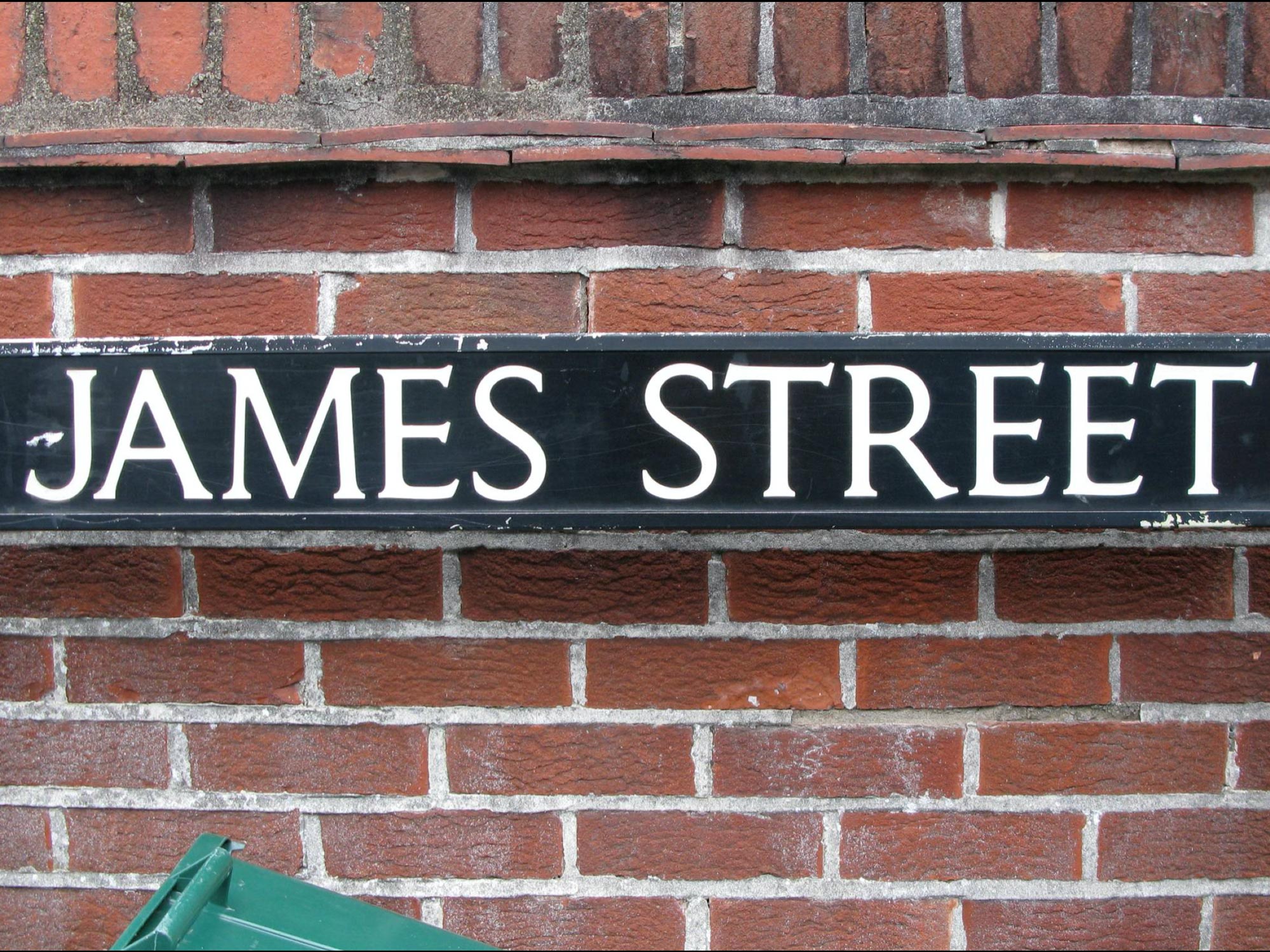

Some people would say they live on James’ Street. Others say that proper-nouns need to add the ‘apostrophe +s’. So they live on James’s Street.

Both are ‘correct’ but you need to use one or the other. There is no reason why a street would ever be called James Street.

A street sign in Oxford. It is missing a apostrophe but where would it go?

Even those people who do add ‘apostrophe +s’ to proper nouns agree that Jesus is exceptional. So they would refer to Jesus’ disciples.

To recap on names…

A chemist shop, run by a man called Duncan might be called Duncan’s Pharmacy.

If a chemist’s shop was owned by the Duncan family it might be called The Duncan’s Pharmacy.

But if the family name were ‘Duncans’ (plural) then it might be called The Duncans’ Pharmacy or The Duncans’s Pharmacy.

But there is no reason why it would ever be called Duncans Pharmacy.

And, if Duncan sells his shop and Tarquin buys it, it can still be called Duncan’s Pharmacy even though Duncan no longer possesses it.

A shopfront with a sign that we know needs an apostrophe but can’t be sure where it should go.

Even more exceptions…

‘To show where letters (or numbers) have been omitted’ is the overriding rule so, if adding a different type of apostrophe might confusingly look like an abbreviation, we find a different solution.

For instance:

Who’s always means ‘who is’; we use whose? to mean ‘possessed by whom?’

It’s always means ‘it is’; its (with no apostrophe) is used to mean ‘belonging to it’.

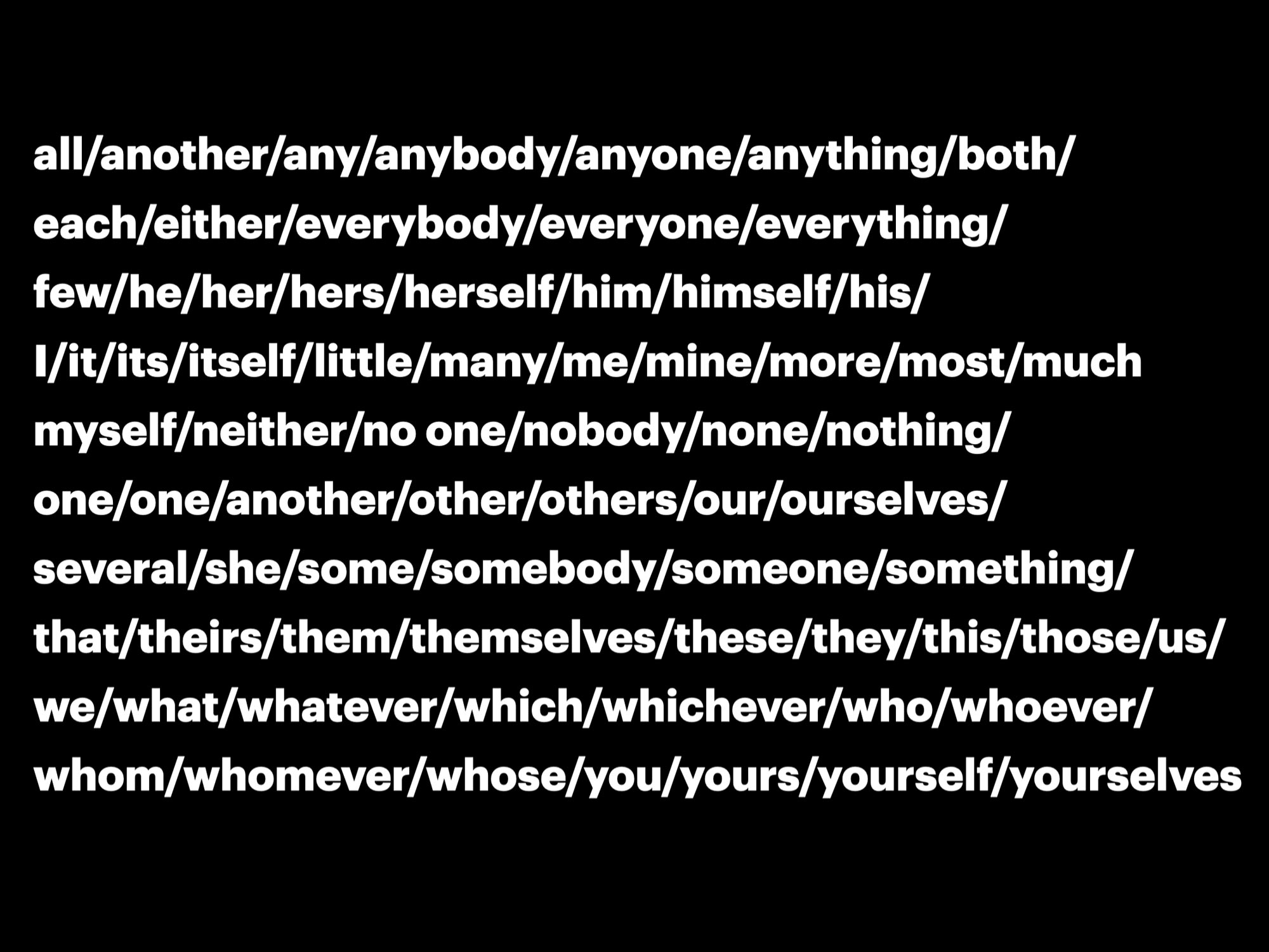

And that brings us to the scary sounding ‘possessive pronouns’…

Pronouns are substitute words for a name or noun. English has more than 70 pronouns.

Some pronouns use the normal apostrophe rules. We might write: that is someone’s property; it is somebody’s prized possession.

But there are eight special ‘possessive pronouns’ for which we don’t add ‘apostrophe +s’.

These three have special new words:

‘that property is mine’ not ‘that property is my’s’.

Or ‘that mistake was his’, not ‘that mistake was he’s’.

And ‘whose mistake was it?’, not ‘who’s mistake was it?’

And these five where we just skip the apostrophe:

‘that triumph was all hers but the victory was ours’

‘I was standing in its doorway but theirs was not a house I wanted to be in; I wanted to be at yours’.

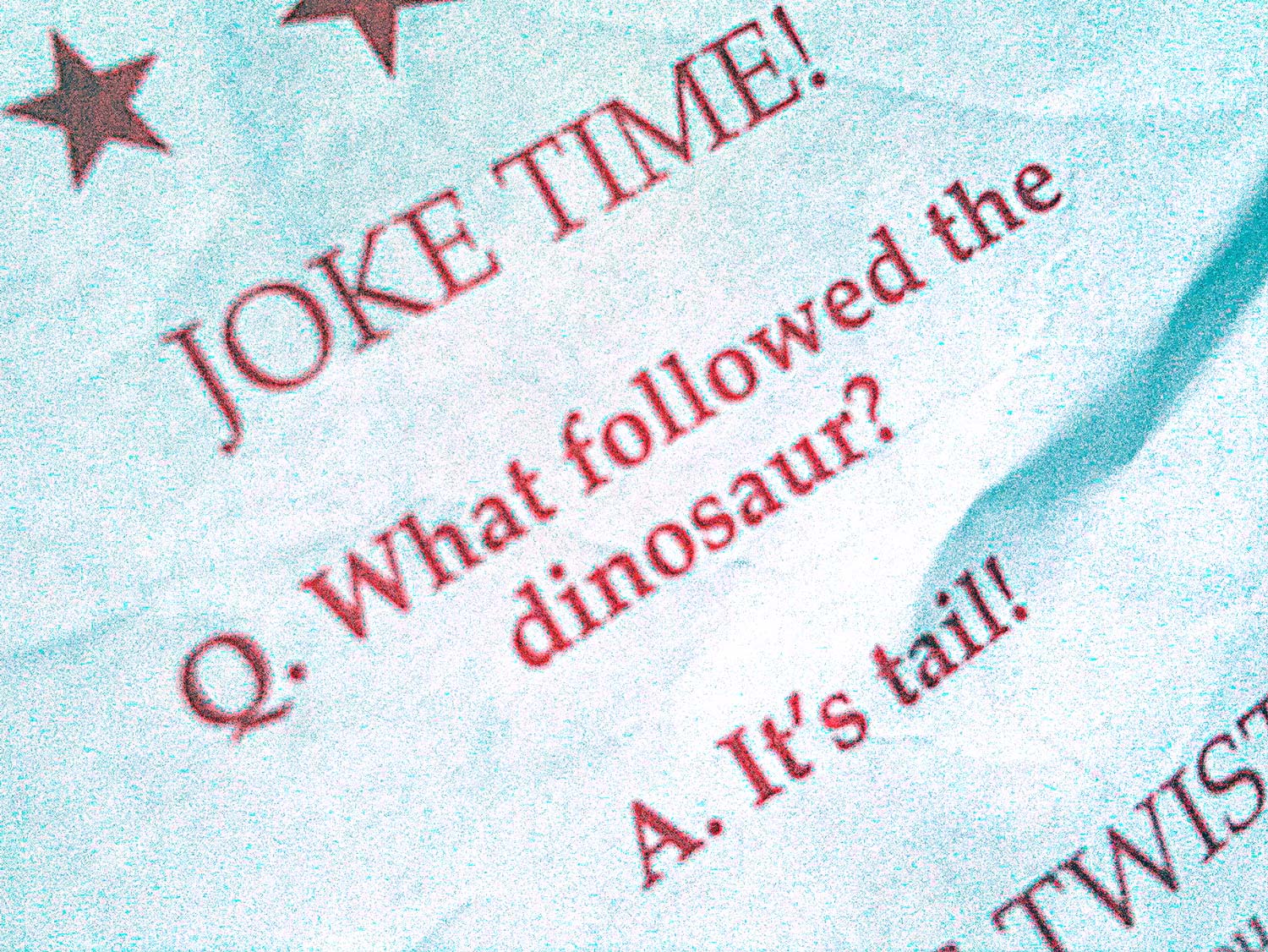

A cracker joke loses its meaning by adding an apostrophe.

Three less common uses

To indicate heritage in some names

I’d always assumed that a name like John O’Kelly is an abbreviation of ‘John of Kelly’. Suggesting that John was born in Kelly. This seems to make sense but apparently it’s not true. The ‘O’ is actually an approximation of the Celtic word ‘au’ which meant grandson. It’s interesting to know but probably doesn’t affect our apostrophe uses.

To express multiples of letters, symbols and some short words

This is a tricky one and easy to get carried away with. I suppose the rule is that we add an apostrophe, to mark the gap before the plural ‘s’, only when it aids meaning.

We write: ‘there are two p’s in apostrophe’. Because ‘there are two ps in apostrophe’ is confusing.

Equally, we might write: ‘what are the do’s and don’t’s of punctuation?’

But there is no need to add an apostrophe to indicate multiple teas.

A Café menu. Someone has tried to cross-out the rogue apostrophe.

To indicate quantity (including time)

I think this is the trickiest of all. It’s really just an extension of the ‘possession’ principle.

So…

‘After a month’s practice I mastered the apostrophe‘.

‘In two days’ time the baby will be three weeks old’.

The trick is to imagine the number is singular and read is out. Would it still have an extra ‘s’? If so, it should have an apostrophe too.

‘In a day time’ is odd because ‘day’s time’ is correct.

‘One weeks old’ is odd because we’d refer to a ‘one week old baby’.

What is an apostrophe?

The history of the apostrophe, in English, is fascinating and complicated. But I’ll leave you to do your own research into that.

What is worth addressing is that it is a distinct shape.

It is (usually) the same as a closing single quote mark (like the shape of a 9 or a comma in the air) and distinct from a vertical mark (or inverted droplet) which we use to indicate the imperial measurement of ‘feet’ or ‘minutes’.

Most of us just use the quote mark key and let our computer make a best guess as to which symbol we mean.

The sign on a school, with ‘minute’ mark rather than an apostrophe.

But if we want to be sure then we need to make a bit more effort. On a Mac, that means pressing Alt + Shift + closing square bracket. And on a PC… I don’t know, I never use PC’s, sorry.

To wrap-up, I reiterate that there’s no need to get to hung-up about apostrophe use. As long as your reader knows what you mean then that’s OK.

But sometimes it is important to be clear about your meaning: you don’t want people to think your stupid.

Even so, everyone makes mistakes. I spotted this sign at the British Museum where their Director is interesting enough to be called ‘entrancing’ but I don’t think that’s what they meant.

And finally, to show why the position of an apostrophe can be important, here are some very similar sentences with meanings that shift as the apostrophe moves:

We sat at our designer colleague’s desk means: ‘we sat at the desk of single designer who was our colleague’.

We sat at our designer’s colleague’s desk means: ‘we sat at the desk of a single colleague’.

We sat at our designer’s colleagues’ desk means: ‘we sat at one desk with several colleagues’.

We sat at our designers’ colleague’s desk: means: ‘we had several designers, they had one colleague, we sat at their desk’.

We sat at our designers’ colleagues’ desk: means ‘several designers had several colleagues, we sat with those colleagues at a single desk’.