Through the timed ’rounds’ on a boxing clock, Sean Mahoney tells the tale of his growth into adulthood. For our April Cog Night, we walked to Deptford to hear his story and soak in the atmosphere of the gym.

Until You Hear That Bell at The Albany

Let’s start with a spoiler warning. I don’t seem able to write a review without giving away the end. Sorry.

So… I’d seen Daniel Kitson recommend the writing of Sean Mahoney; maybe it was in one of his irregular, rambling, disjointed emails that, if you don’t already receive, you should sign up for. If Daniel Kitson recommends something then that’s good enough for me.

Walking from our studio towards The Albany in Deptford.

But when I suggested that our March Cog Night should be spent watching a boxing-based, one-man play, I’m not sure everyone was convinced. It was probably the lure of the venue being within walking distance of the studio that tipped the balance and meant people agreed with my second-hand recommendation.

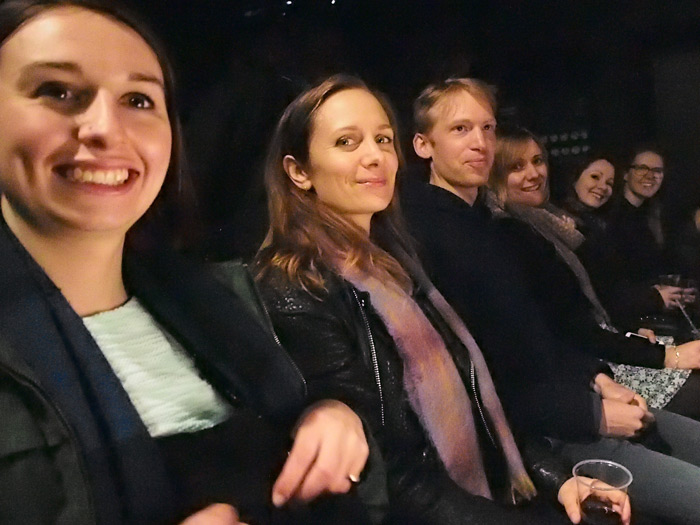

In the foyer of The Albany.

Until You Hear That Bell is written and performed by Sean Mahoney (and directed by Yael Shavit). Sean is an accomplished performance poet with the credentials to prove it – winner of the Literary Death Match in both London and Dublin, and once a member of the Roundhouse Poetry Collective.

The Cog team in their seats, waiting for the bell to ring and the play to start.

With that kind of background, you’d expect a bit of swagger so it was a surprise when a shy looking young man wandered into the small black box studio space (with folding chairs and a roof that you can see daylight through) in his socks and a tracksuit zipped up to his mouth. He seemed off-balanced – “I only just found out…” he mumbled as he took his place and checked his props. I thought the comment was about being joined by a BSL interpreter but he’s been in touch, via Twitter, to tell us it was actually about the space being plunged into darkness as he walked out.

In the corner of the room, a boxing clock counts down in three-minute rounds and one-minute rests. It’s relentlessly regimented, providing a poetic discipline and whipping the story into neat shapes.

An electronic whistle marks time periods. Sean performs the narrative. Occasionally it’s punched out with the alteration of a performance poet but most of the time it’s quietly spoken set scenes, drawing you into his story, introducing you to the characters, jumping you through time.

We begin with Sean’s first trip to the gym. His dad has brought him. We imagine the cliché of a pushy father, toughening up his son, but Sean’s dad is kind, encouraging and supportive. Sean tells us how much he cries and we’re reminded what it’s like to be a child in an adult world, keen to please, confused by everything, knuckling down and taking your punches.

As the rounds progress we hear more about home-life, and the break-up of his parents, and how much it means to his dad to see Sean at the gym. The pressure ratchets up as Sean progresses and grows – his first gum shield, the first time he beats his sparring partner, his first bout, his first win.

By now, we’re in the ring with him. We can see the red-faced men in the Essex venue, we can smell the sweat and feel the heat, while they’re shouting the odds and screaming the ‘kill ‘ims’,

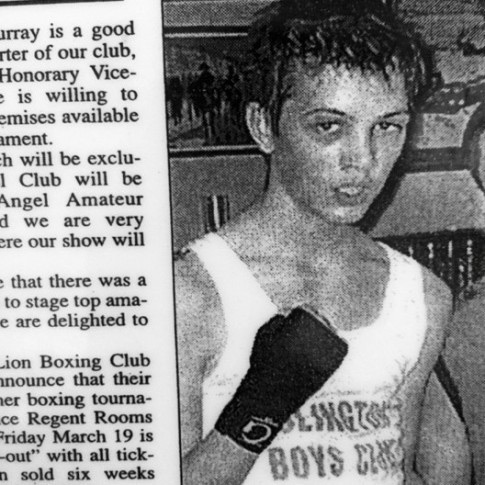

Photo: © Olivier Rudkin

He’s good, good enough to follow the dream of the men in the gym, to turn pro.

The march of the clock persists and Sean is now a young man, a young man who’s failed his exams and has to join the ‘apprenticeships or BTEC’ queue.

We hear him make the choice that will define his future: “what, I get to do drama every day?”

He’s trying to balance two conflicting worlds.

My favourite three-minute scene is him running from a drama rehearsal to get to the gym. Running to the bus stop, then the next, then the next; desperately looking over his shoulder for a bus that never came.

It’s heartbreaking when we all know that he’s going to give up the boxing. We’ve lived the past ten years with him, we know the tragedy of letting down his father, and we all know he’s got to make his own choices. The clock is stopped and he walks away from the gym.

Jumping forward and Sean’s signed himself up for an open-mic stand-up in the pub next to his old gym. He pops in to revisit that life. All eyes are focused on the young hopeful in the ring, a glimpse of what could have been.

He thinks they won’t understand his choices. He tells them that it’s his friend that’s doing stand-up, he’s here to support him. That takes guts, they tell him, unaware of the irony.

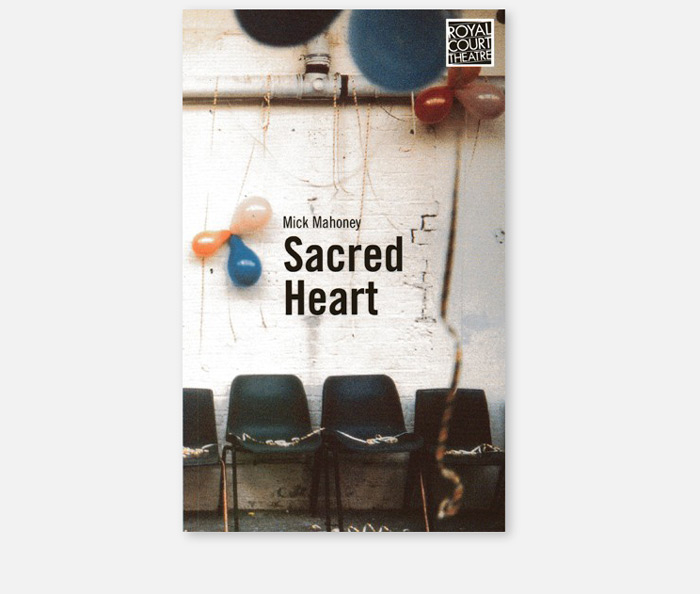

And then, for me, the twist in the tale. ‘How’s your dad doing?’ ‘Yeah, well. He’s got a new play at the Royal Court’. ‘Royal? Must be fancy’.

What? Sean’s dad is a playwright?

Well, yes, it seems that Sean’s dad is Mick Mahoney, the playwright who draws from his own youthful experiences of London’s criminal underworld; the man who penned an infamous piece, for Time Out, about fashion and football hooliganism, that captured the zeitgeist of my youth (as I cowered, terrified by it all).

The play text of Mick Mahoney’s first play at Royal Court, in 1999.

Those two words ‘Royal Court’, full of nuance and reference, were funny and telling in so many ways. I don’t want to take anything away from Sean’s writing or performance; on the contrary, that tiny revelation gave a whole new context and poignancy to all that had gone before.

The play wasn’t without a few stumbles (and some mumbled fourth wall breakers that I loved). And, although I admire and commend the Albany’s commitment of having a BSL interpreter, it did sometimes get in the way of the performance (in such an intimate space). Again, Sean’s been in touch to say how much he enjoyed sharing the performance with Jacqui the interpreter; thinking back, there was a very sweet moment when she took hold of his kit bag as he lowered it towards the floor.

The play was first performed (to rave reviews) at BAC, last summer, and now Sean is taking it on a national tour. If you are anywhere near one of the venues, I definitely recommend you go and see it. It’s a great play: witty, insightful and true; performed with an engaging energy by a man with real talents.

The Cog team, angelically lit outsie The Albany in Deptford.

Check out Sean’s website for updates about his work and the tour.