We went on our first (virtual) Cog Night in a while. Ed gives his account of this poignant Zoom-based performance.

My White Best Friend (and Other Letters Left Unsaid)

When lockdown started we put a pause on our monthly cultural outings. We were still adjusting to life at a (social) distance, and although there were all sorts of cultural experiences available, few were live performances we could enjoy together. But as we all got used to the ‘new normal’, more and more live experiences were being staged online by brilliant theatre companies and cultural organisations. By July, a Cog Night was long overdue.

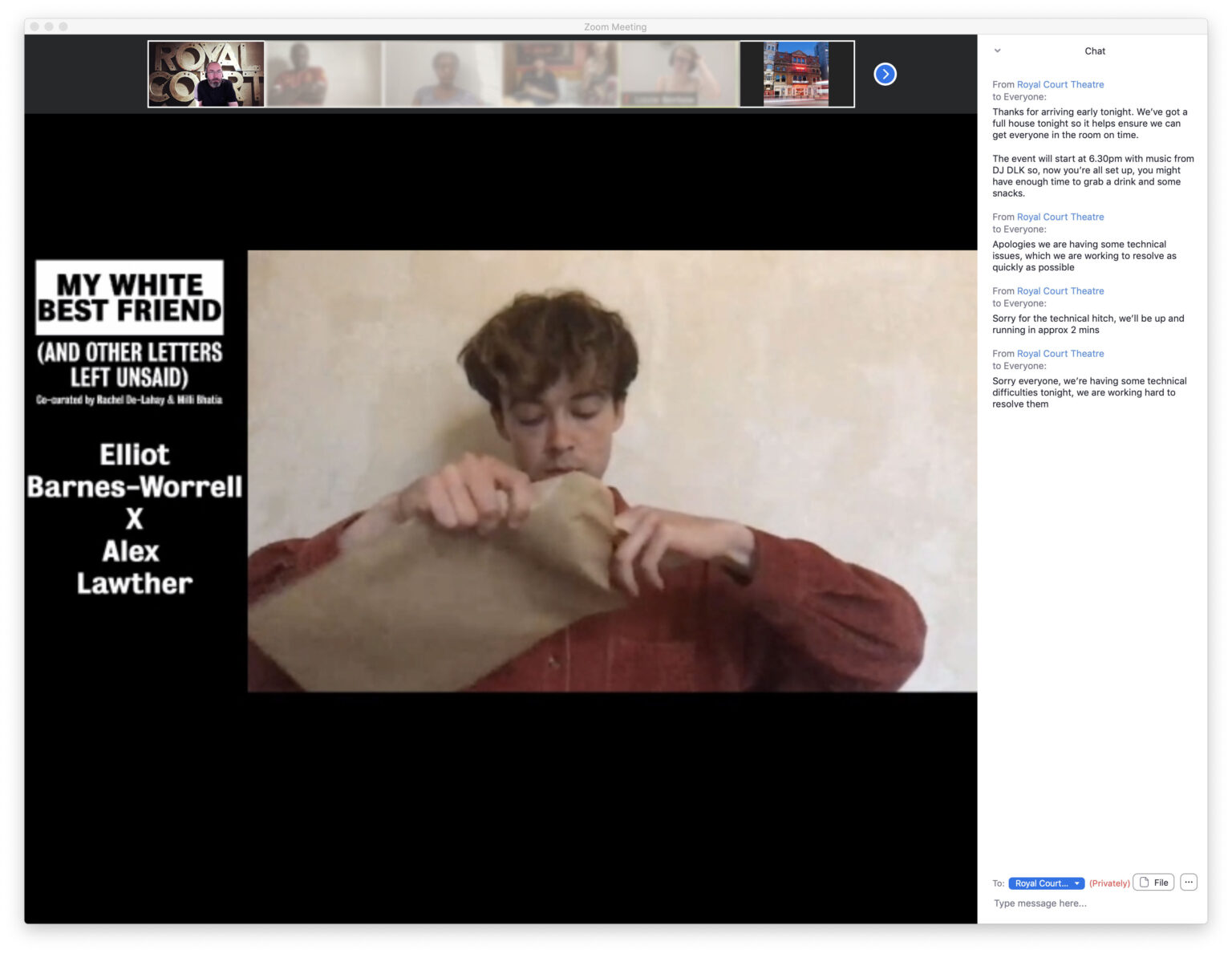

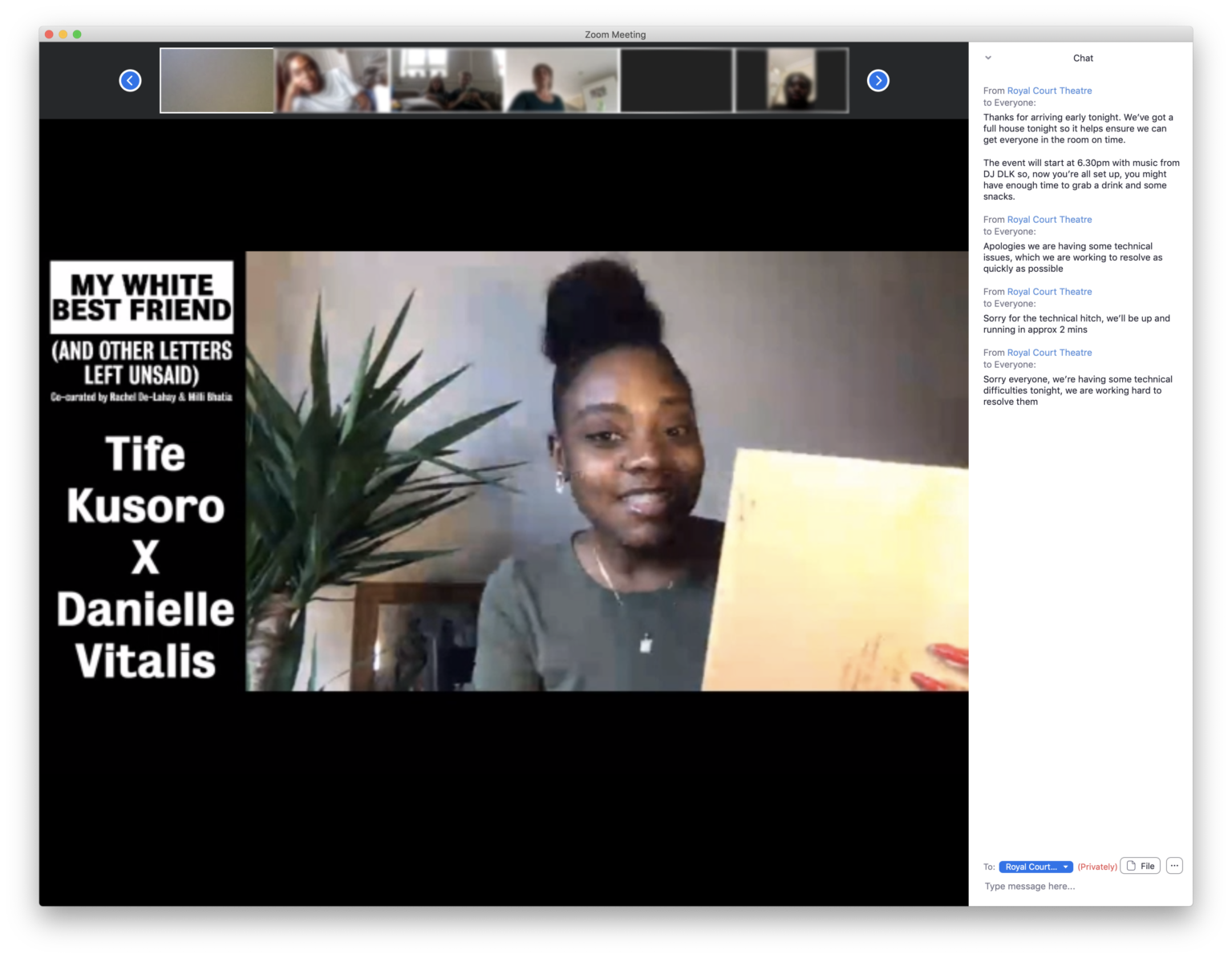

For our first outing in a long while (and our first virtual Cog Night) we attended the Thursday night performance of My White Best Friend (And Other Letters Left Unsaid), an online version of Rachel De-Lahay and Milli Bhatia’s festival.

The format of the performance was simple. Three actors read scripts they haven’t seen before to a live audience. It’s a gimmick that’s been used effectively before in shows such as Manwatching, White Rabbit Red Rabbit, and An Oak Tree, but here it’s sharpened into a means of examining racial tensions, microagressions, and emotional labour.

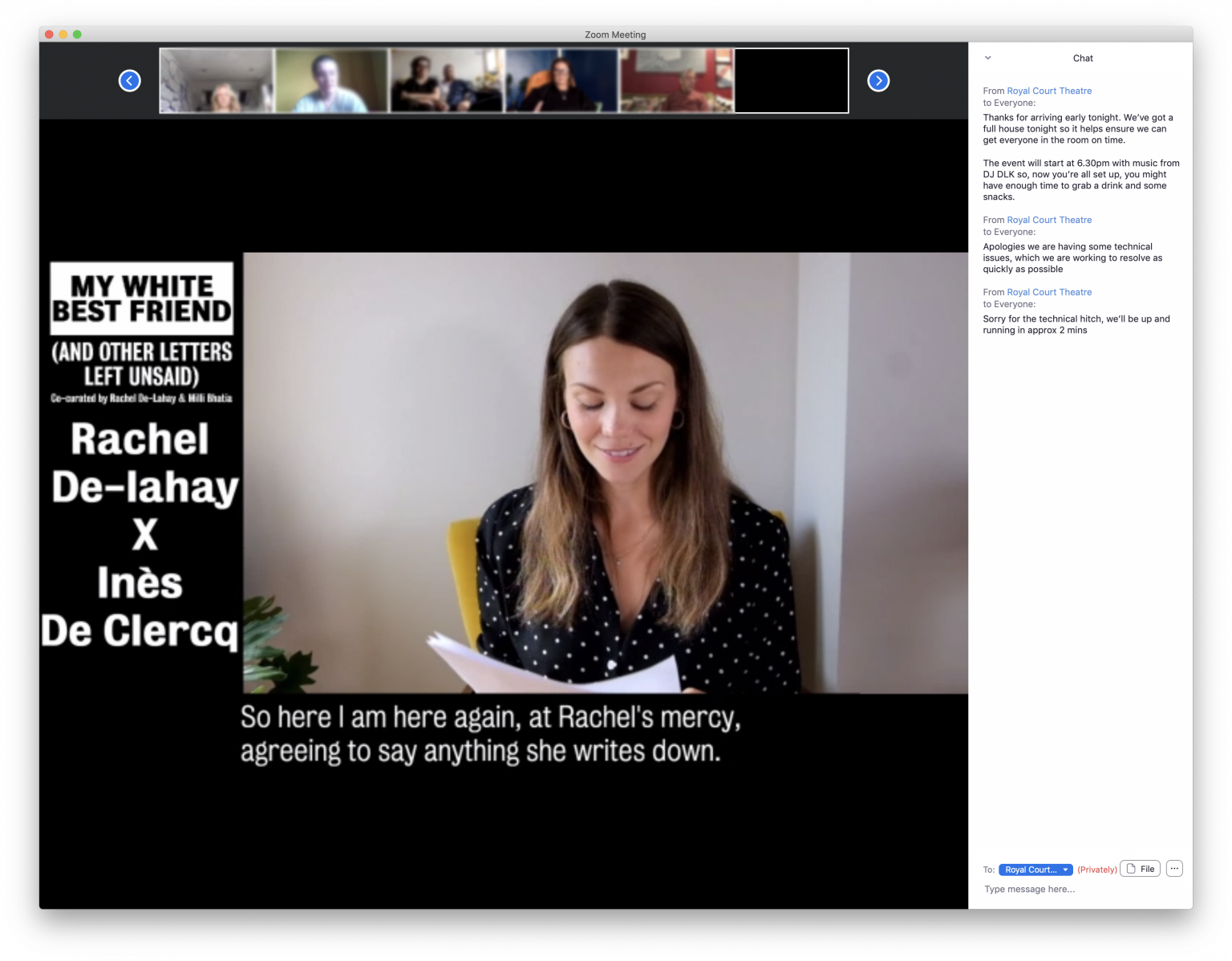

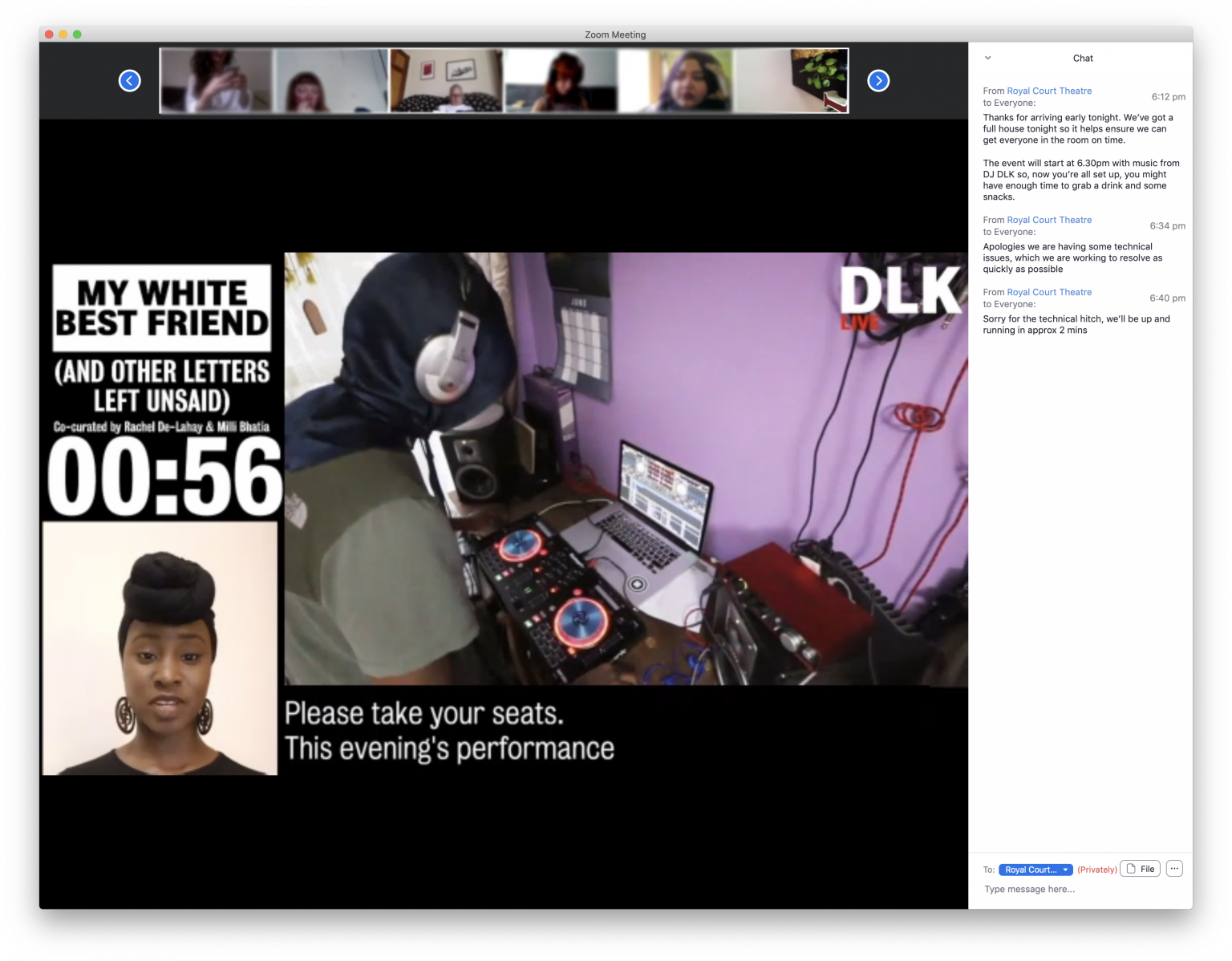

We attended My White Best Friend on Zoom, which seems to have become the favourite platform for hosting live events in lockdown. Whilst there were a few technical difficulties and false starts, Zoom lent the evening an extra kind of intimacy that the auditorium of a theatre lacks. The audience (700 strong) were encouraged to turn cameras on. So the main performance was accompanied by a gallery of strangers, responding to deeply moving writing from the comfort (and sometimes uncomfortable intimacy) of their homes.

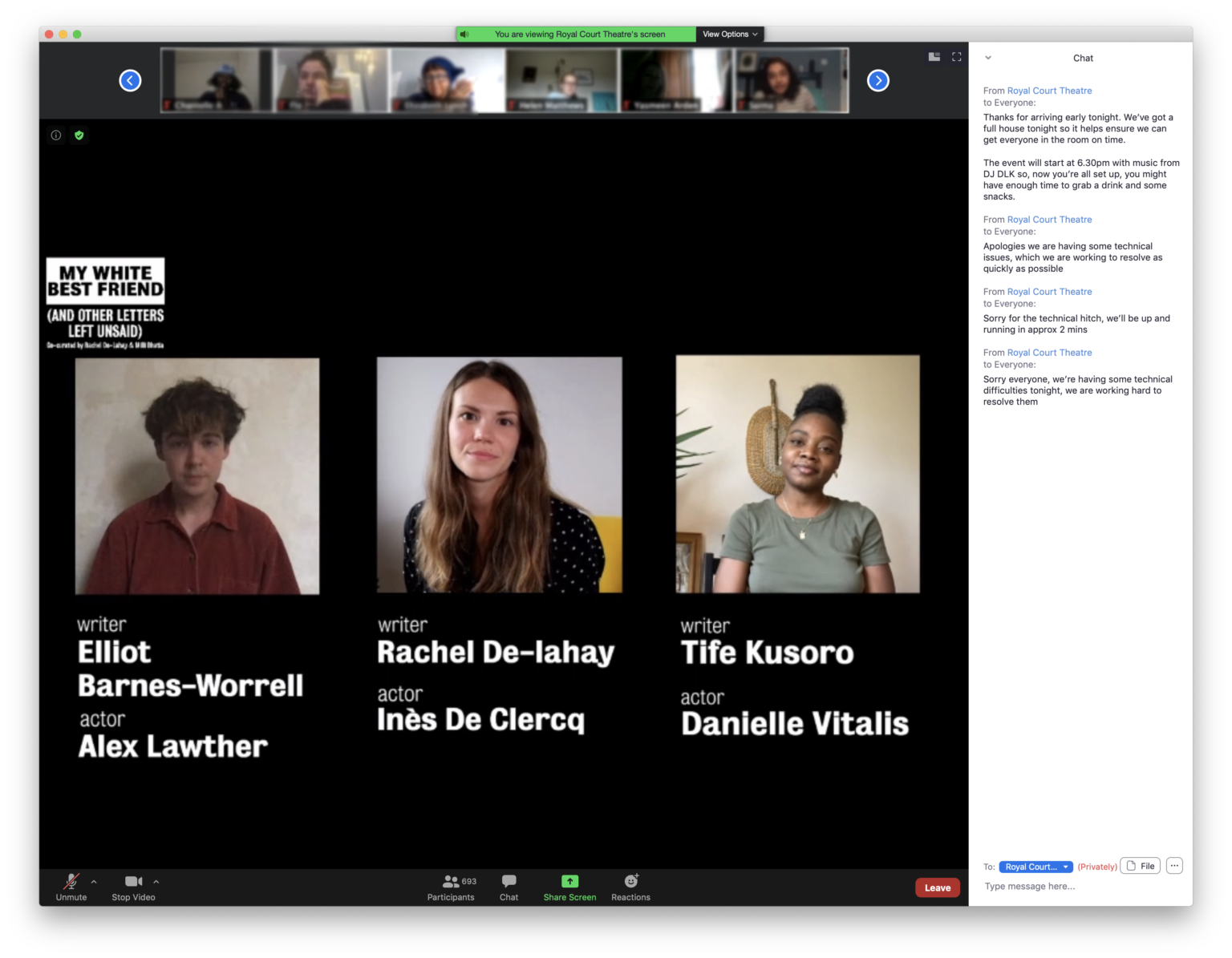

Apart from a pre-recorded opening letter written by Rachel De-lahay and performed by Inès De-Clercq, the writers and performers changed each night. On the Thursday night we went to, Alex Lawther and Danielle Vitalis were reading letters by Elliot Barnes-Worrell and Tife Kosoro.

In his letter Elliot Barnes-Worrell addressed a white family member and close childhood friend. As the pair grew up, Barnes-Worrell’s friend began to exploit his Blackness for kudos amongst peers at school. Lawther’s boyish performance was touching. He found the wit in Barnes-Worrell’s writing and was visibly moved at the most painful points. It was not a polished, well-rehearsed reading, but what was lost in finesse was gained in emotional impact.

Tife Kusoro’s letter described a dream she had in which she met a Black girl from her childhood. Her lyrical writing described the isolation of being a Black girl in the British education system, with tender accounts of friends and allies from her school days. Vitalis’s moving performance powerfully articulated Kusoro’s depiction of the racism she experienced at school.

My White Best Friend rightly didn’t pull any punches. In her opening letter De-lahay called out the Royal Court (who were hosting the festival) for not doing enough to support Black creatives on and off stage. And with half of the tickets available for free via the Black Ticket Project, the festival presented a better and more open way of making theatre.