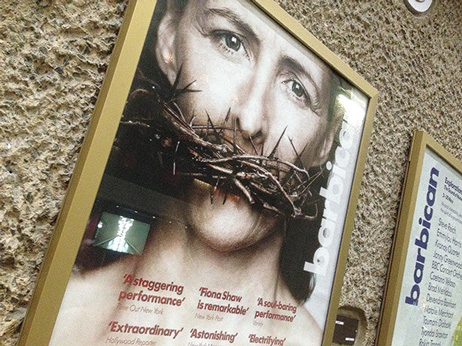

In the latest of their collaborations, Deborah Warner directs Fiona Shaw in a solo performance at the Barbican Theatre. Shaw plays Mary, in an adaptation of Colm Toíbín’s novel about the mother of Jesus.

The Testament of Mary

Taking my seat, in the gods, I felt proud to be part of a society that is tolerant of such a challenging play. Putting words, angry words, doubting words, into the mouth of ‘the blessed virgin’ must be challenging to the church. But the talk of those around me (including a priest), was of openness to the play, a willingness to experience first and judge later. It might have made a neater review if I could report that my pride came before a fall. But it didn’t, the play was remarkable and I heard nothing but praise from the theatre congregation.

The Virgin Mary is a mystical, mythical presence in our lives, adopted and reinvented by different branches of Christianity, growing in significance and gathering a narrative, imposed upon her. But she barely speaks in the bible, we hear very little about her and even less from her.

We all know Mary from countless paintings, carvings and sculptures; she is a ubiquitous icon in our society. Colm Toíbín’s play, he gives her a voice. The Testament of Mary is a first hand account of a mother, a woman who mourns the loss of her son, first to the path he took in life and then the life that was taken away.

Mary tells to us about ‘the one you want to hear about’ (she cannot bring herself to utter his name). She remembers him as kind and charismatic, he was gifted, he could have done anything. Instead he gathered a group of misfits and got himself noticed and executed for his trouble.

Before the performance, the audience is invited onto the stage to walk around Tom Pye’s set. They shuffle like processing pilgrims, not sure why they are there or what they are looking for. Then Shaw appears amongst them, she makes her way to a large Perspex box and sits inside, draping herself in the blue shawl that immediately transforms her into the Virgin Mary of renaissance art. It’s a powerful and discomforting visual made more haunting by a discordant chiming audio (that echoes throughout the play)

The box rises and Shaw emerges, distributing candles to the crowd and ushering them back to their seats before picking up a vulture and walking the stage with it on her arm.

The bird is an allusion that Toíbín’s script keeps referring back to. Whilst her son is being crucified, Mary is distracted by a man passing live rabbits to a caged bird. The bird rips out the soft underbelly and plucks out each eye, leaving the dead rabbit uneaten on the floor.

With the audience back in its seats and the bird taken from view, Shaw is back, centre-stage, to tell her tale.

Men have come to write down her story but its clear that the men aren’t interested in her or her grief (for her long dead husband as much as her recently departed son). They want propaganda, stories to help to save the world – ‘All of it?’ she mocks in her own Irish lilt, ‘all of it!’ she shouts back in the men’s voices, assuming the harsher edge of Northern Ireland.

Mary tells to us about ‘the one you want to hear about’ (she cannot bring herself to utter his name). She remembers him as kind and charismatic, he was gifted, he could have done anything. Instead he gathered a group of misfits and got himself noticed and executed for his trouble.

Shaw brilliantly morphs between the characters of Mary’s recollections: a shawl on one shoulder and a raised hand transforms her into the Jesus we immediately recognise.

Mary tells of her trip to Cana, to the wedding of a distant relative. She didn’t want to go and felt tricked into being there, being at the centre of so much attention, attention that she knew would lead to trouble.

She isn’t convinced by the water into wine event but it is the raising of Lazarus from his grave that she knows has sealed the fate of her son. And for what, even if it is true, Lazarus is in a trance, recognizes no one and will soon be dead; if he is brought back to life it is only for long enough to say his last goodbyes. Is this the revolution that they seek; is it worth it?

But the wheels are now in motion, her son is beyond Mary’s reach, he has become a symbol to those that want change. She knows that to fulfill their plan he is going to be martyred in their name, he has long been a grown man and she has been powerless to stop the tragedy that has unfolded in his life.

As the play draws to an end, Shaw plunges, naked into a pool beneath the stage. Drawing from the water, Mary tells of how she fled from the site of the crucifixion, and of the nights on the run with Mary (Magdalene), stealing clothes and food. Hugging for warmth they shared a dream, ‘I didn’t know you could share a dream’. In their dream he was reborn, he spoke to them.

She is clear, it was a dream, but ‘they’ wrote it down and turned the dream into their reality. Mary is angry, grieving, broken by what ‘they’ have done, and if anyone asks she tells them – ‘it was not worth it… it was not worth it’.

This is a wonderful play. I could have done with a little more introspection and a little less throwing of furniture, and I do find the actory pauses in Shaw’s delivery a little affecting at times but these are tiny distractions in an otherwise flawless performance.

And, as we shuffled out of the rows, I heard nothing but positive views from those around me, including those in dog-collars; fair praise indeed.