Our November Cog Night was online. From our respective homes we visited a concrete car park in Bradford, to hear from three young Muslim men about their passion for custom cars and the troubles of their lives. Michael gives his take.

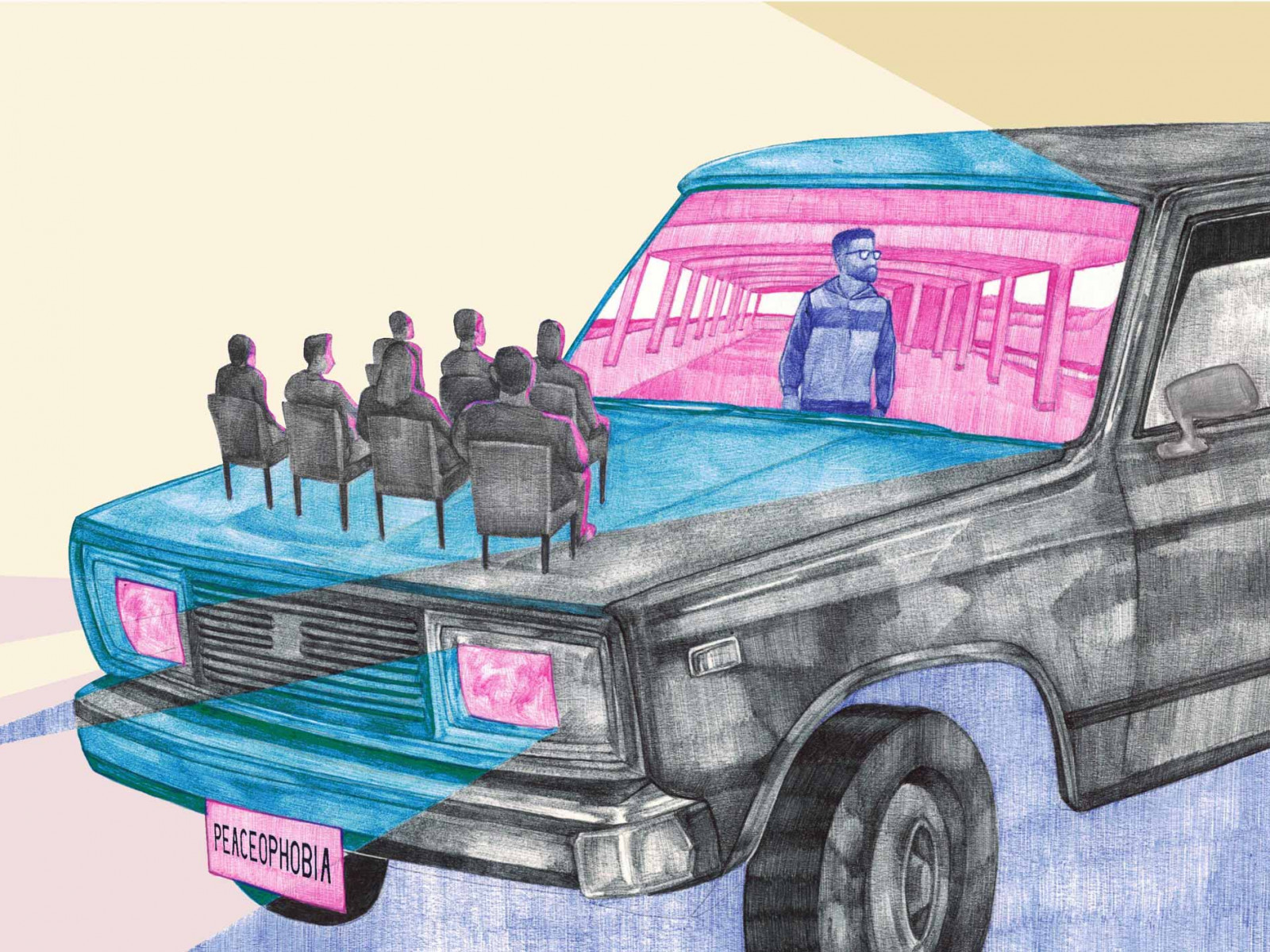

Peaceophobia – Fuel Theatre

For our November Cog Night we opted for an online show, partly so we could include our distributed show and partly because we’d been excited by this particular show but it didn’t tour close enough for us to visit. Oh, and we love Fuel Theatre and we’d happily engage in anything they do.

We paid for the stream (actually it was a donation-based contribution) which gave us access for a few days. But we decided to make an event of it by all beginning at the same time. That sort of worked but with no travel to enforce the deadline, several of us had staggered starts.

Peacophobia was (and hopefully still will be) performed in car parks to audiences on scaffold-constructed seating.

We often hear people in the arts talk about authentic voices and lived experience. However, although usually well intentioned, we all too often hear those experiences retold through the lens of ‘proper’ theatre and mannered actors.

Through Peaceophobia we get a different take, a chance to glimpse into the subculture that feels alien, sometimes hostile, often impenetrable from the outside – the custom car fanatic. And the setting is all part of that process, taking audiences outside of theatres, and closer to the arenas where life’s real dramas are happening, all around us, every day.

The play (if that’s still the correct word) was an idea that emerged via Speakers’ Corner, a collective of young, Muslim women in Bradford. The 2001 riots felt like a societal schism from the outside; on the inside the city recast its young, male population as troubled and trouble.

The original concept was a car rally in the city centre. A chance for young men to get together and share their passion.

The pride shown in that subculture sparked the thought that a play could bring those stories to a broader audience, to shine full-beams on everyday racism and harassment, and to show young, Muslim men refocusing their energy, money and time into a hobby that brings them joy and camaraderie.

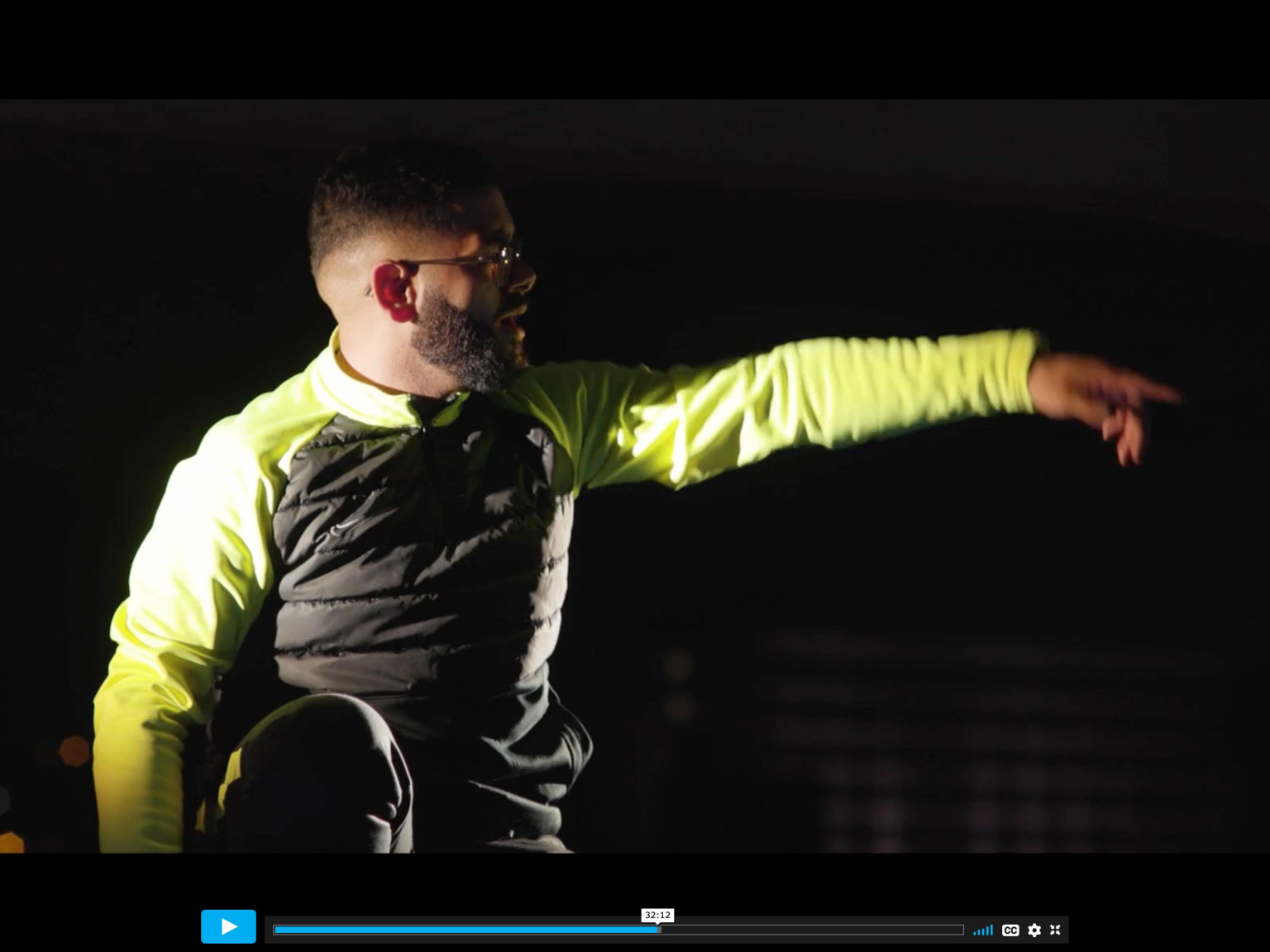

The three protagonists (all with day-jobs) contributed their own stories, while women and girls from Common Wealth served as co-directors alongside the artistic director, Evie Manning. The narrative was pulled into a play structure by Zia Ahmed, who is a regular contributor at Royal Court and Bush Theatre.

We hear from each about the ways they are regularly stopped, profiled and categorised.

‘Released without charge’ becomes a mantra as the characters are routinely taken in for questioning, stripped of dignity, held overnight and let back out into the light of day. We see the distress on their faces when the police impound a car because of some oversight. They aren’t worried about getting it back (they know they will eventually), they are worried that a lack of respect and care will damage this most precious part of their lives.

Again and again, they accept the situation, go back and rebuild – “We go from scratch, we build it all back”.

The show is far from perfect. There’s an awkward lack of exposition and the rhythm of the writing doesn’t always suit the natural delivery of the performers. But these quirks are outweighed by the overall experience.

For a relatively small scale production, the values are high. Special praise needs to be given to the sound team. It must have been a nightmare to keep the actors microphones balanced as they moved around and got in and out of cars, let alone mixing the music and (excellent) soundscape in a concrete car park.

As the show ended you could see how thrilled the actors were, and how emotionally moved the audience were. Sitting at home, the show had a similar effect on me. If it’s made available again, do stream it. If it tours, anywhere near me, I’ll be there.

Illustration by Itziar Barrios for our Cultural Calendar.