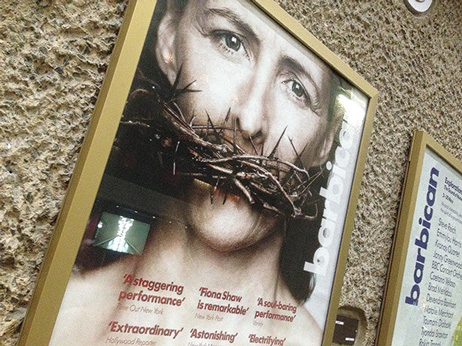

As part of the 2018 London International Mime Festival, the Belgian company FC Bergman brought one of their early shows to the Barbican Theatre for the first time. Michael talks us through the wordless experience.

FC Bergman 300 el x 50 el x 30 el at Barbican

When I mentioned to my friends that I was off to the London International Mime Festival they looked askance. They imagined a beret-wearing Frenchman trapped in an imaginary box.

What I saw at The Barbican could not be further from that cliché.

Well, FC Bergman (no, I don’t know why they sound like a football team) do come from Belgium so maybe they speak French. They didn’t speak so I don’t know.

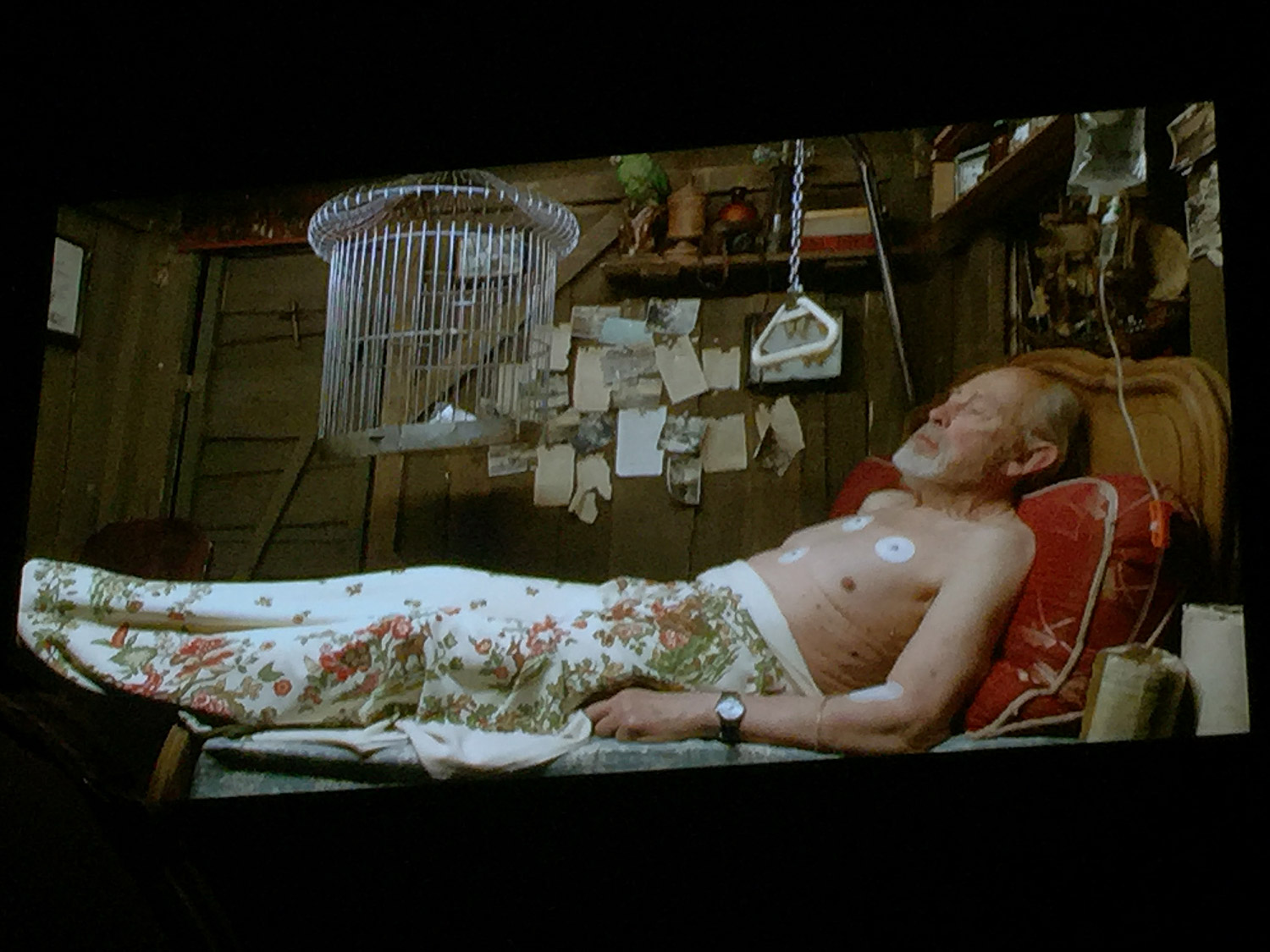

Shuffling down my row, excusing my presence to pointy-kneed people, I glance towards the stage and see, in front of the curtain, a huge projected image of an old man lying in a bed.

As I find my seat I look back to the stage and there’s another man. He’s on a stool, smoking, staring out, seemingly oblivious to our presence. In the sky above him I notice that the old man’s image is moving, breathing.

FC Bergman © Kurt van der Elst

Everyone’s in. There’s a weird collective moment when we all feel we’ve heard a signal and we are all immediately silent. But our quiet is premature. House staff are still checking for empty chairs. They stand either side of the stage like bouncers. Staring.

We continue to hold our tongues until, at last, the curtain goes up.

Visually, we’re not too surprised by the set. We’ve seen the publicity images – a circle of ramshackle shacks, their doors closed to us, in a clearing in the woods.

Perhaps two seconds later it hits us. A sensory wave rolls from the the stage and through us all. This isn’t the make believe of theatre, they’ve brought the forest. Dozens of real trees and a stage full of damp leaves. It already feels special.

It’s quickly clear that the projected image (still in place) is a live feed from a camera unit, filming through the open back of the first shed.

The old man gets up, stumbles through his door and onto the stage. And as he shuffles through the leaves and into the forest, a violin stabs into Vivaldi and the camera begins to loop around the other buildings, on a track that circles the stage.

Through each open back we are given glimpses into some peculiar lives.

FC Bergman © Kurt van der Elst

A family watch as their matriarch gorges. A woman forces her (presumably) daughter to practice the piano, a man’s flaccid masturbation to a phone sex-line is ignored by a woman on the loo, a gang of burly men bully their weaker compatriot, and a single man lights bangers in a scale model of the cabins before us.

By the end of the camera’s first loop the old man is gone but the cycle of oddities is just getting going.

With each clockwise encounter these examined lives become more and more bizarre.

FC Bergman © Kurt van der Elst

At times the mood is comically dark, at others it is just surreal. A caged pigeon is ‘killed’; the gorging mother eats her dining table; the pianist tries to keep time to her mother’s tapping rhythm but her mother keeps nodding off and waking up; a deviant woman gives birth to a family of sea-shells; the burly men play William Tell with darts and stab their prey in his eye before all turning into seagulls; and the man with the bangers lets them off in time to beats of the the now waltzing piano playing.

FC Bergman © Kurt van der Elst

And as more revolutions keep the stories spinning, the darkness takes a tighter grip.

In the pond, the fishing man drags the carcass of a sheep from the water. It is raised into the air on a wire and with lights to the side we see (and hear) the water cascading into the pool below.

The trees behind the village rise into the air, turning their world upside down.

All the villagers come out of their sheds to stare into the sky at this portentous spectacle.

FC Bergman © Sofie Silbermann

They stare in silence until the dripping has calmed, and then return to their cabins.

But by now darkness has taken its hold. A stolen moment between the piano girl and the banger boy turns nasty in the woods. She pretends to run away with him but instead leads him into a gathered circle of villagers. The burly men nail him into his cabin and the sound of bangers is replaced by a single pistol shot as the cabin begin to burn.

By now the camera crew is pushing harder and the opening piano bars of Nina Simone’s Sinnerman begins to play.

One by one the villagers emerge, each with a bucket of water.

“Oh sinnerman, where you gonna run to…”

Each villager plunges their head in and throws their head back in time to the music.

“So I run to the river. It was bleedin’, I run to the sea…”

The lights catch the arcs of water above each of them.

“So I run to the Lord. Please hide me, Lord…”

They’re kneeling now, each forcing their right arm into the water and pulling it out in rhythmic concert.

“But the Lord said go to the Devil…”

The water describes a sideways arc before falling to the ground

“So I ran to the Devil. He was waitin’…”

FC Bergman © Kurt van der Elst

All the time, the camera crew are racing around the set, faster and faster, more and more frenetic. The buildings flash by, and inside we see that its raining inside them all. There is water everywhere.

“I cried, power, power (power, Lord)…”

Now the camera is off its rig and moving from the back of the stage, through the villagers towards us. And the villagers are bouncing, trance-like in time to the music.

“Power (power, Lord). Power (power, Lord)…”

The chanting music goes on for an age – it’s a very long song.

It’s exhausting just watching them. But they go on and on and on bouncing.

“Power (power, Lord). Power (power, Lord)…”

They are joined on stage by the backstage crew. They are all bouncing, leaping to the music, soaked by the set.

“Power (power, Lord). Power (power, Lord)…”

They keep bouncing through the excruciatingly drawn-out ending to the song.

And then they stop.

And we clap and cheer and take to our feet.

We’re applauding their stamina, their commitment, their craft, the sheer intensity of the experience.

So what was it all about? Does it matter?

The show’s title 300 el x 50 el x 30 el refers to the measurements of Noah’s Ark, as very specifically noted in Genesis. I’ve read interviews since where the FC Bergman team say that they imagined a devoutly religious community, in panic, waiting for the impending flood. I’m not sure I got that from it but that really isn’t important.

This was a show of sensation, of moods, of feeling, of unsettling silence broken by laughter and snorting disgust. It was a play without words but packed with emotion. It’s an experience that will stay with me for a very long time.