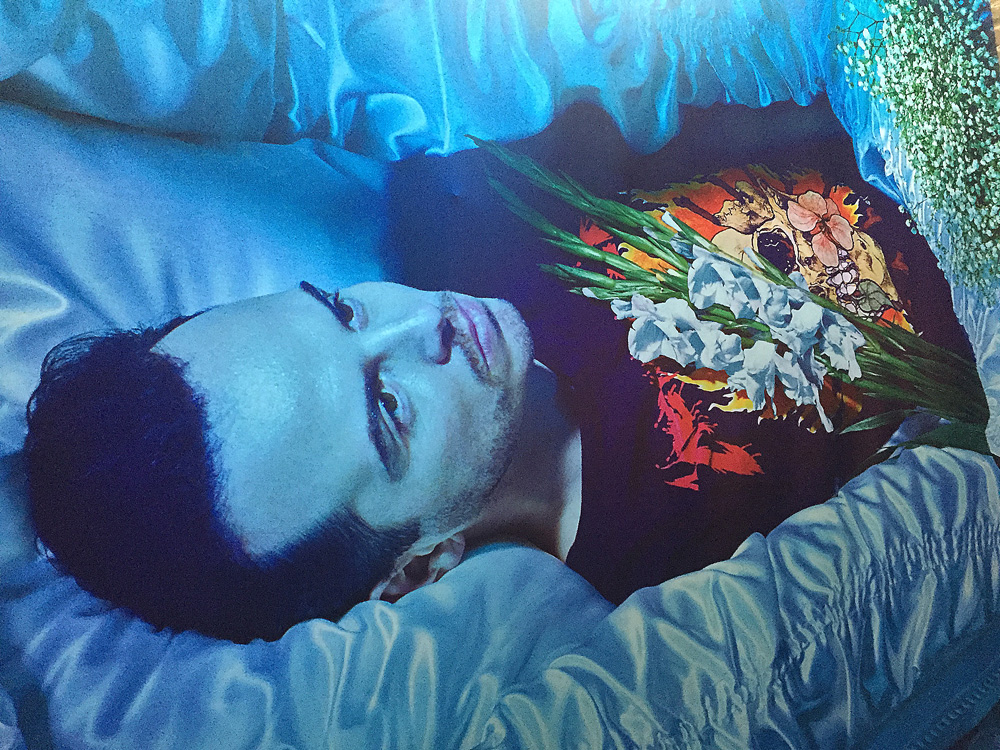

The brilliant Andrew Scott gives us his Dane in a new production directed by theatrical wunderkind Robert Icke. Michael settled in for a long night at Almeida Theatre.

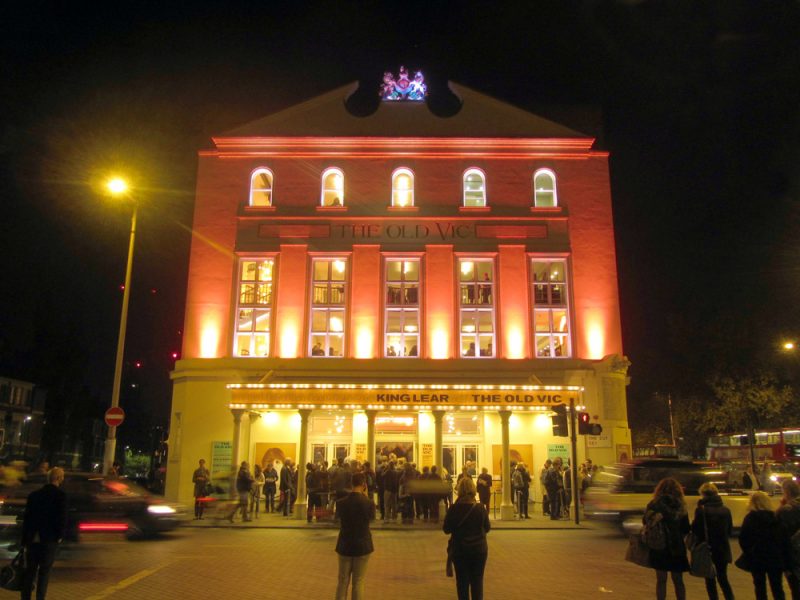

Hamlet at Almeida Theatre

Nobody told me that this was a four hour production. I could have found out, I probably should have guessed by the ‘7pm prompt start, no latecomers, no readmissions’ email I’d received the day before. If I’d realised I might have readied myself a little more adequately – sorry to those around me if my rumbling stomach cut through the pin-drop silences.

I settled in to my seat five minutes before the start and was reminded (by the theatrical whispering of the thespian stalkers behind me) of the many recent ‘celebrity’ castings of Hamlet: Cumberbatch, in the fastest-selling Barbican production, David Tennant for RSC and BBC, and Maxine Peake in a gender-blind version at Royal Court. My audible auditorium buddies had seen them all and were here to ogle Sherlock‘s Moriarty in the role. There’s nothing wrong with that, I love that it brings in new audiences, especially when the acting is genuinely world-class.

I was there as much for Robert Icke’s direction as for Andrew Scott’s good looks. Icke is a phenomenon – the man behind Headlong’s production of 1984, that’s just announced a Broadway transfer, and the visually exceptional The Red Barn at National Theatre (my favourite show of 2016). He didn’t let me down here, although his approach was a lot more nuanced on this small stage.

Set in a modern Danish castle with Scandi-sofas, sliding doors isolate the stage from the background events. Lighting switches our attention from silent, joyful wedding celebrations to the foreground internal turmoil of a son betrayed and bereft. Juliet Stevenson is brilliant as Gertrude stepping between those realities: a queen, a compassionate mother and a woman who’s found new love, late in life, and is enraptured by the charms of her dead husband’s brother (Angus Wright). She did also fall foul of the set on the night I was there; she let out a whelp after striding face-first into a huge glass door. The show went on around her.

The staging and design really help to bring context to the text. Video is used to great effect throughout the production. In a freezing cellar, reluctant security guards are terrified by the image of the dead King, walking the grounds, captured on CCTV. For the staging of the play within the play – The Mousetrap – TV cameras and paparazzi flashes remind us of the family’s celebrity status, and stay to focus on the new King as that action mimics his own – we read guilt into his face, frozen on a huge screen above the stage. The fatal duel is even given context through a fencing bout with full ‘costume’ and a digital scoreboard.

Despite the great ensemble cast and original staging, the star of the show was, of course, Andrew Scott. He delivers every line as if it’s his own, it’s a remarkable performance. At moments, he’s a surly son who’s been practising his remarks to cause maximum hurt to those around him. At others he’s frail, vulnerable, paranoid, unsure of his sanity. He turns on emotions with the flick of a switch: delighted to see old friends, wary of their intentions; angry, frustrated, betrayed, confused.

I’m usually irritated by the pausing and affectation of ‘acting’ but Scott makes it all feel so natural; he’s so good at his craft that we forget that he’s acting at all.

I absolutely loved this production. My only criticism was the extra long pause of a second interval. It felt unnecessary, broke the tension and meant that a fair few people had to bolt in fear of missing their last trains.

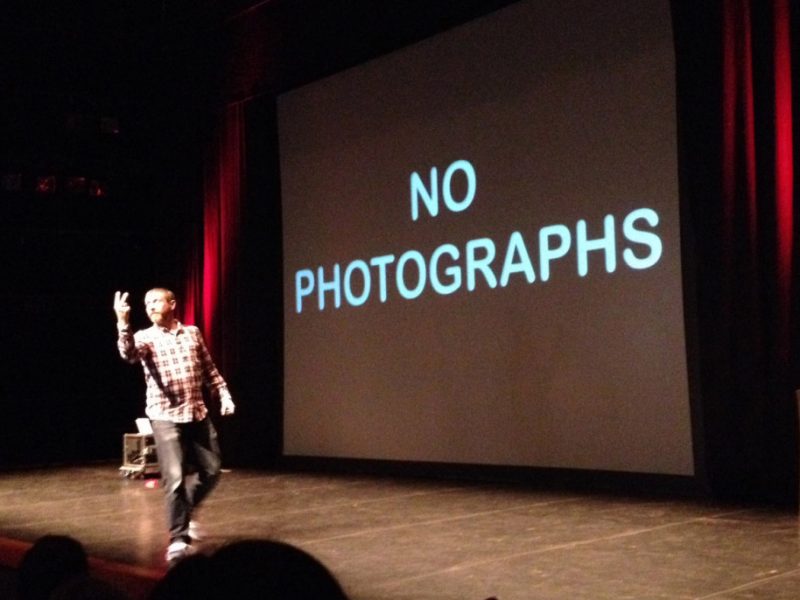

As far as I know it isn’t being recorded for a big screen release so do try to see it on the stage. Although you’ll struggle to buy a ticket online, Almeida are great at releasing day tickets and there are often returns – it’s well worth the risk of queuing for one.

Addendum, April 17: Hamlet is to transfer to the West End’s Harold Pinter Theatre with a run from 9th June to 2nd September.