Martin Creed might not like the label ‘conceptual artist’ but I’m struggling to think of a better way to describe his art. In this retrospective the Hayward Gallery is filled with concepts.

Martin Creed at Hayward

Creed’s career is like the result of a frantic afternoon of brainstorming (or whatever the PC equivalent would be): what if I painted but couldn’t see the canvas, what if I could only reach the canvas by jumping, how about I use video, or sculpture, or found objects, or…?

The theme of the show seems to be ‘conceptual themes’. The bulk of the show is about things: things in rows, things in size order, variations of the same things shown together, things balanced on other things. There are tapes, balls, bricks, light-bulbs, glass samples and even rhythms – the opening room has 39 metronomes, each set at a different speed, creating accidental patterns like a Steve Reich work.

Even Creed’s cataloguing system is conceptual; each piece is given a consecutive number (he started at Number 3) as well as an often hilariously functional name. My favourite – Number 158 ‘Something on the left, just as you come in, not too high or low’.

By far my favourite piece was the monumental kinetic sculpture that almost literally hits you in the face as you enter the show.

This retrospective covers all of Creed’s career, from his O-Level self-portrait through his Turner Prize winning lights turning off and on (and doors opening and closing, and curtains opening and closing). There’s an awful lot of the ‘is it art?’ type of work (for instance, work Number 79: Some Blu-Tack kneaded, rolled into a ball and depressed against a wall), there’s some video (including the close-up of a penis, becoming an erection, displayed against the London skyline, filled with, er, men’s erections) and there’s some sound (including a speaker playing farty noises).

He’s taken over the whole space; everywhere in the Hayward is filled with Creed’s work. The lifts have been Creedified, the outside terraces have installations, even the toilets have fun additions.

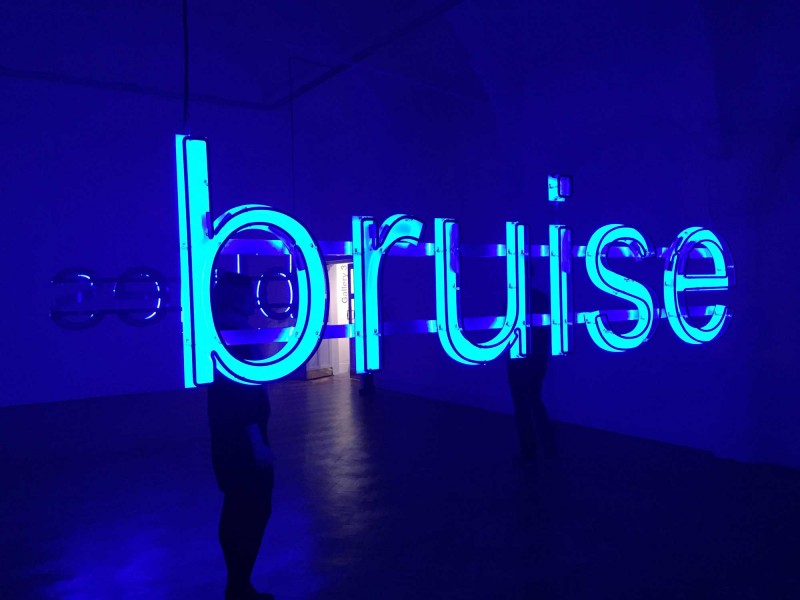

By far my favourite piece was the monumental kinetic sculpture that almost literally hits you in the face as you enter the show. The word ‘Mothers’ in six-foot neon, atop a spinning girder. Made to feel small and fragile by ‘Mothers’ may be a far from subtle metaphor but it was still a powerful statement. And I couldn’t help but marvel at the lack of any health and safety notices as I walked below this massive beam of steel, ducking slightly each time it threatened to decapitate me.

I also found myself worrying about the clean-up after the show. He’s applied huge patterns of black paint directly to the walls and chopped down integral concrete balustrades that are going to be a nightmare to replace.

With his constant need to keep trying something else it’s easy to dismiss Creed as a lightweight, against the long-term career commitment of someone like Antony Gormley, who brings an academic rigour and monumental scale to his messing around with different materials. But that is too simplistic a view. Yes, Creed is funny but that’s part of the point, isn’t it? Where Gormley’s Hayward retrospective featured a cloud-filled room, where visitors were lost in existential nothingness, Creed filled his own glass box with latex balloons, where visitors just seemed to laugh and play (and take covert photos to use as their Facebook avatars).

What’s the point of it? asks Martin Creed in the knowing title of this retrospective. That title seems to have upset many an art critic; the art world seems to love his self-mockery but the critics appear to view him with a mixture of scepticism and frustration: is this all just an elaborate practical joke? Martin Creed is perhaps the artist who most readily personifies the Emperor’s New Clothes view of art. Art critics fall over themselves to say he’s no Duchamp but I’ve not read a single review that doesn’t reference him.

Like so many of contemporaries (including the YBA’s like Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Michael Landy) Creed seems to be both revelling in self-mockery and taking himself a bit too seriously. He’s simultaneously telling us that art is about the idea (and anyone can have ideas) and that his ideas are somehow more valid than our own because his are shown in galleries.

For me, that is the most interesting aspect to Creed’s retrospective, and the careers of so many of his contemporaries. They were in the right place at the right time, with the right connections and networks, and the perfect mix of accents and manners. Art movements used to be revolutionary, rejected by the establishment only to be embraced by later generations. In the 20th century, that process of acceptance seemed to be constantly accelerating to a point where it may even have overtaken itself. Creed’s career would not, could not, have existed at any other time; his is not a revolution but he is the perfect example of art evolution.

On your way out, you’re forced to face the question again: what’s the point of it? I’m not sure, but it made me think, it made me marvel and I had lots of fun laughing at myself, laughing at the art that might well have been laughing at me.