Day five, the final day of a week of cultural tourism in Berlin.

Cultural Berlin – Day 5

Our National Museums pass had run out so we decided to explore some private exhibitions on our last day.

We began the day in a shopping centre (Alexa in Alexanderplatz). At the top of the building, through the food courtward and up an escalator, is the LOXX miniature world.

This is a vast, open plan room, with an enormous model trainset, weaving its way through an incredibly detailed model of Berlin. Geographically perfect areas, merge with fantasy zones, concert arenas and even a mountain where aliens have landed; there’s a government zone with the Reichstag, the Brandenburg Gate and interchangeable speeches by Kennedy, Reagan and others; there’s even a working airport.

The whole room is constantly alive with movement and daylight turns to night every twenty minutes. We spent at least an hour in awe of the detail and the humour to be found in every tiny scene, especially the details they’d added for Halloween.

From Alexanderplatz we negotiated the S-Bahn to get us to Museum für Gegenwart (Museum for the Present) at Hamburger Bahnhof.

The Hamburger Bahnhof has been a museum/gallery since 1906; it ceased to be a railway station two decades before.

The main feature of the gallery is the vast central space, devoted to temporary exhibitions. Whilst we visited, they were showing modern (post 1960s) sculptures under the title Body Pressure.

The exhibition was a great mixture of the conceptual and the figurative. Amongst many others, there were video pieces by Marina Abramovic and Gilbert & George, figurative pieces by Ryan Gander and Martin Kippenberger, and conceptual works by Briuce Nauman and Franz Erhard Walther. We had great fun taking part in some of the work, and marvelling at Marc Quinn’s Shithead.

The rest of the gallery is split between two wings and two floors. I think there were different individual collections in different areas but I’m not sure we ever figured out the layout or what went where. We did stumble across some incredible large-scale pieces by Joseph Beuys, plus rooms full of Warhol and other luminaries of 20th century art.

After a short break in the bizarrely popular and luxurious restaurant/café we got the S-Bahn in search of the Story of Berlin Museum.

Rounding off our cultural tour, The Story of Berlin was a bit of an amalgam of many of our previous experiences: it was accessed through a shopping mall, it felt like some of its original ambitions had been abandoned to limit running costs, and it felt a little tatty around the edges but it was a wonderful museum.

The main attraction for us was that the entry ticket included a tour of a Cold War nuclear shelter. But (presumably to limit staffing needs across the very large second space) access was only via a guided tour and those tours were every other hour.

So, with almost two hours to kill we wandered into what we assumed was a fairly small-scale private museum. We were wrong.

This museum is brilliantly layed out with wonderful interpretation materials to guide visitors through the full history of the city. Every room has layers of information so a visitor can get a quick overview, more context or lots of information by delving into the detail. It really reminded me of the Modern Galleries at Museum of London.

As you’d expect, there is a lot of space devoted to the 20th century, with sensitive and interesting perspectives on the wars, and some original ways of avoiding the mawkish whilst confronting the uncomfortable issues.

The final, large space is devoted to the Berlin Wall. There are actually very few artefacts here (or anywhere in the museum), stories are told through models, text, graphics, sound, video and key historical pieces. It is the antithesis of the Checkpoint Charlie museum that we’d visited on day one.

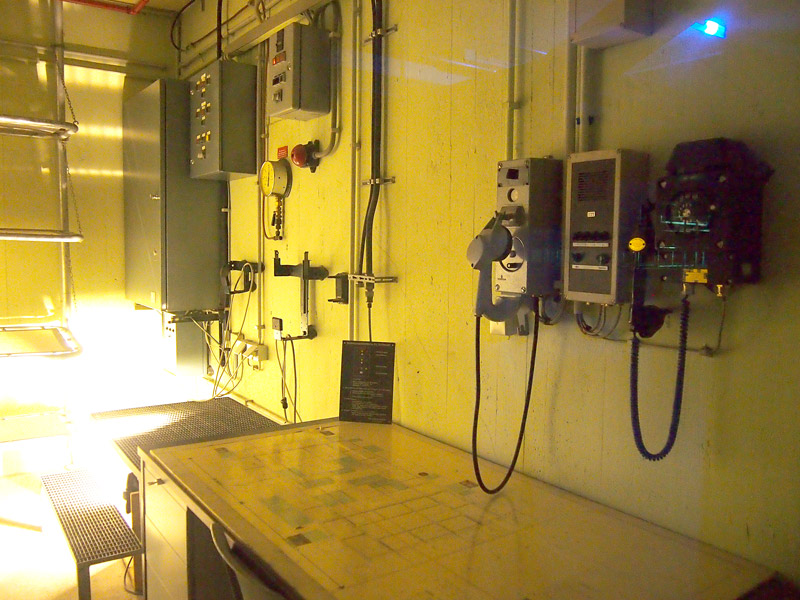

With our timed slot fast approaching we made our way back to our tour meeting point. In a group of about 30 people we were taken our of the shopping centre and into the underground car park, the basement floor of which had been built a nuclear shelter (through very heavy subsidy from the West German government).

The most chilling part of the tour was our entrance. We were locked into the first room which would act as both a decontamination room and airlock, and as the selection point for entry. The bunker held a fixed number of people with no hierarchy, entry was first come, first served. Guards would have looked through viewing screens to count numbers and eventually lock the doors.

The bunker was lit with fluorescent tubes, more for atmosphere than authenticity, and only partly contained the rows or floor to ceiling fold down canvas beds that would have been home to thousands. The rest showed signs (stencilled bay numbers) of the space’s use as a car park, which had presumably seemed more important than a historical archive when the wall came down.

It was fascinating and chilling to be in the space, mostly because, with the gift of hindsight, it was clear that the bunkers (there were many in the city) served no practical purpose. Only a tiny percentage of the population would be able to get into these shelters and those that did only had provision for two weeks underground. Even if it had been safe to emerge and be evacuated, it seems that there was no coordinated plan to pick up the survivors from the city. The bunkers seem to have been little more than a very expensive propaganda exercise.

So, we’d ended our expedition of exhibitions in the way that we’d begun it, with a focus on the Cold War. It’s incredible to see how quickly that recent history has been so readily assimilated into the cultural landscape, and how much appetite there is for people to learn from that past; that has to be a good sign for the future.