Michael ventures beyond the main Venice Biennale sites, in search of activity across the city.

Venice Biennale ’17 – all Venice

I’ve already covered the activities within the two main sites of the Biennale (the Giardini and the Arsenale) so, in this entry, I’m looking beyond and across the city.

Throughout Venice there are dozens (36 I think) of other ‘pavilions’ for participating countries (Partecipazioni Nazionali) in institutes and other temporarily converted buildings. And 23 official Eventi Collaterali scattered above shops, in museums and galleries, and installed in the streets and on building. These are nearly all free to see or enter, even without a ticket.

Laundry in Venice installation by Takahiro Iwasaki

And, of course, there are many, many public galleries, museums and private art galleries in Venice, including the David Hockney portraits exhibition that was recently in London, and a major comeback show from Damien Hirst; I didn’t go to either of those.

I barely had time to skim the surface of the Biennale’s extra events but I tried to dip in wherever I saw something interesting.

Songs for Disaster Relief

We Are the World, as performed by the Hong King Federation of Trade Unions Choir, Samson Young

Just outside the entrance to the Arsenale is Hong Kong’s contribution to the Biennale (not a pavilion, a collateral event – keep up).

Samson Young’s Songs for Disaster Relief attempts to reframe charity singles and their place in the neoliberalism that felt like the norm in the late 20th Century. It was one of the most affecting shows I saw.

The main room is a mass/mess of iconography, a curtain with the lyrics to Do They Know It’s Christmas moves slowly around the jumble, blocking the exits. “Tonight thank God it’s them instead of you” jumps off the velvet material. It’s disconcerting, a jumble of good intention, shared memory, imperialism, myths and fake news.

Through a gap in the curtain, the next room has tip-up theatre seats, directed at a screen, showing a concert. The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions Choir is performing We Are The World. But they aren’t singing, the performance is dozens of forced whispers. It’s the piece that has most stayed with me since returning.

Out into the courtyard there’s a neon sign; we all love neon signs, don’t we? It reads “The world is yours, as well as ours, but mostly yours”.

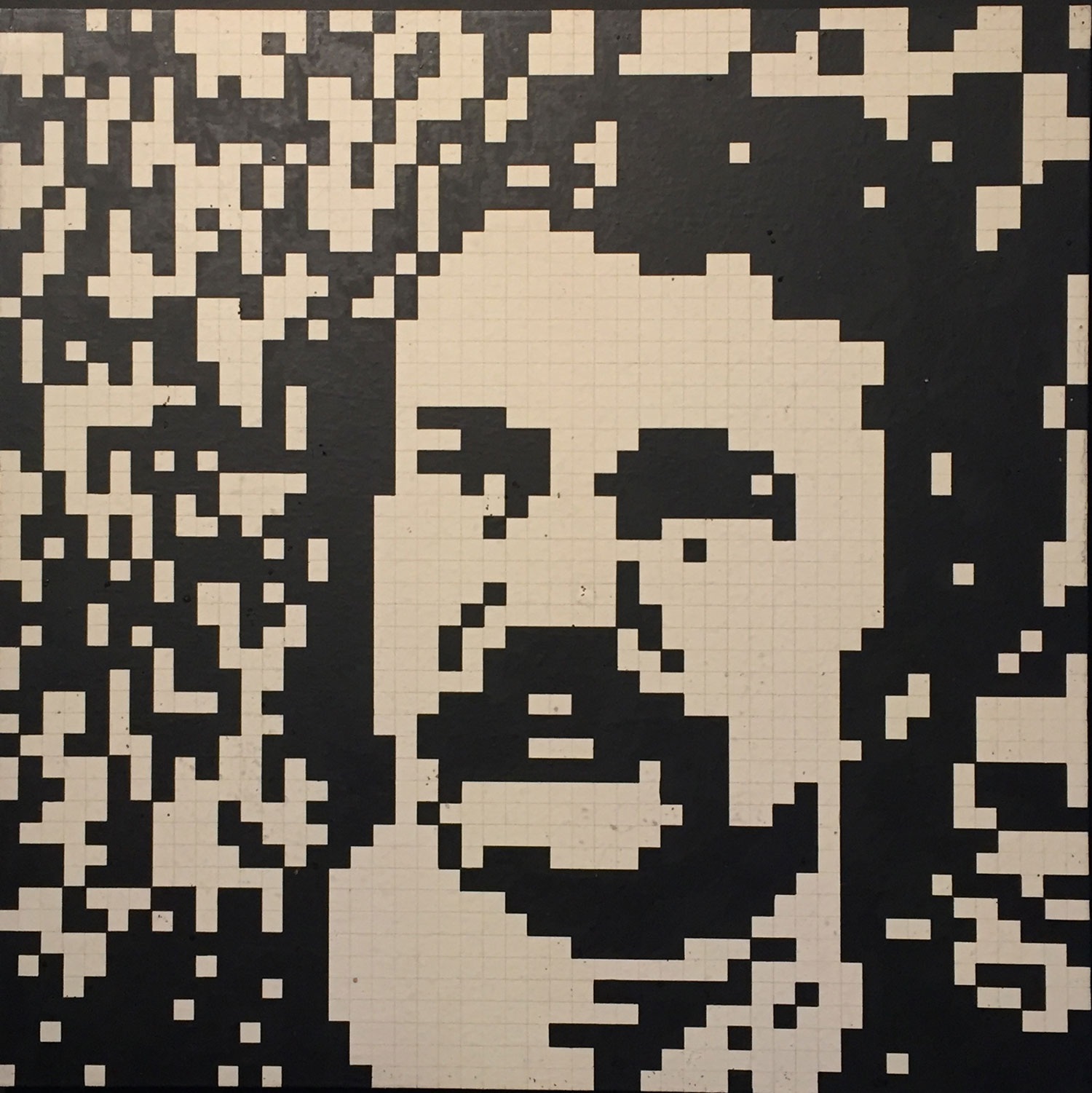

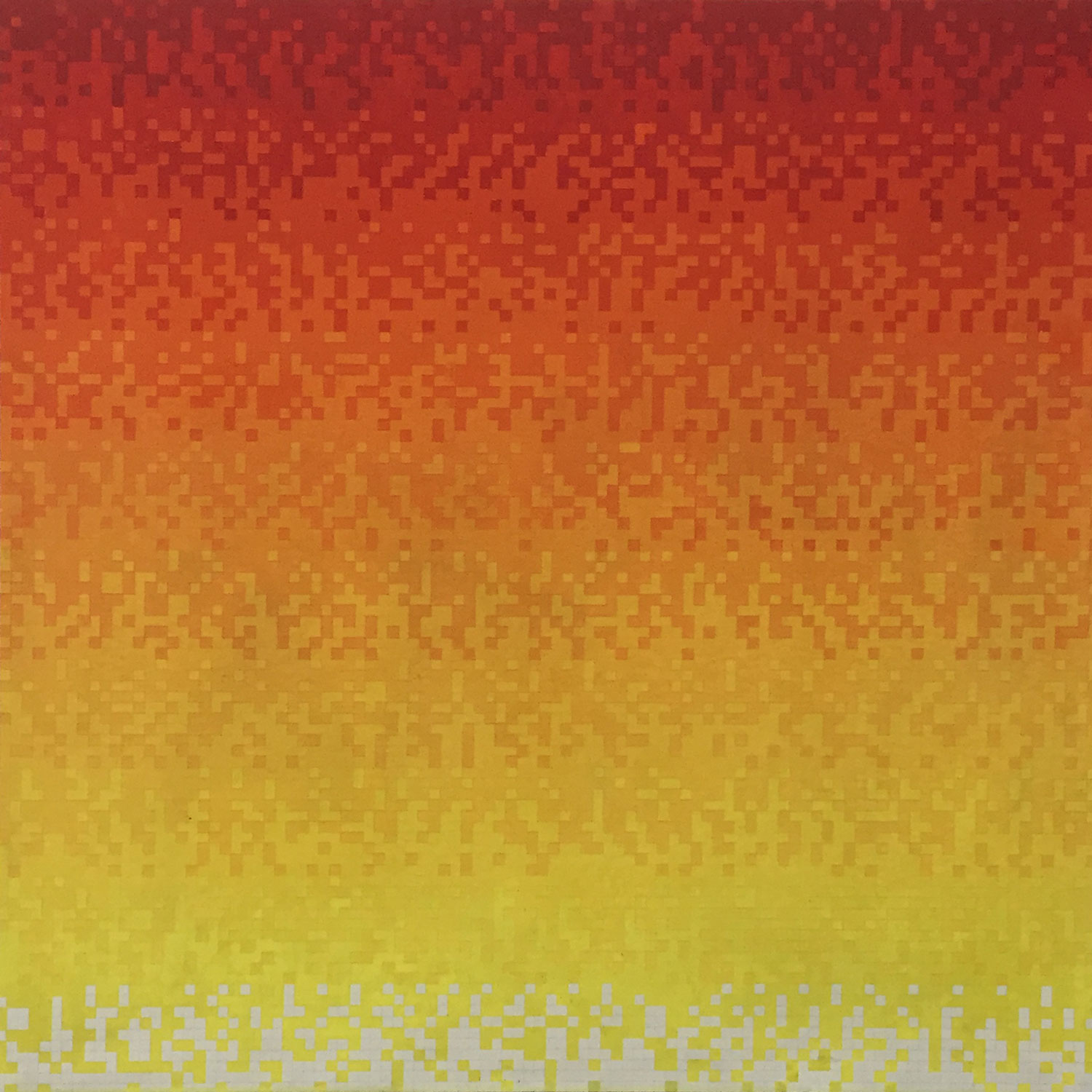

Ryszard Winiarski – Poland

In the beautiful Palazzo Bollani, on the banks of the Grand Canal, Poland staged a retrospective of Ryszard Winiarski.

Winiarski used statistics, chance and rules to create his art, or “attempts of visual representation of statistical distributions”. In his way he was one of the first ever digital artists.

Transition VI. Attempts of visual presentation of statistical layouts. Mutable lot – dice, Ryszard Winiarski

The exhibition features many of his most iconic pieces. Almost everything is in black and white so the occasional use of colour makes a real splash.

And there’s a large area devoted to games, where two or more players follow simple rules and use dice to place black or white squares to create their own art pieces.

Andoran Pavilion

Murmuri, Eve Ariza

Murmuri looks like a beautifully simple concept – bowls formed around what look like mouths in their base, each looks (and sounds) like it’s whispering; clays representing different flesh tones, forming a kind of distribution, like a map.

Of course, the artist has many additional layers of meaning. And so did the room attendant. While I was there, a fellow guest made the mistake of asking the attendant about the work. She may well still be there.

It is a stunning work that stands on its own.

Azerbajan Pavilion

Sphere, Elvin Nabizade

Under One Sun: The Art of Living Together is the gloriously optimistic title for this show. But the politics behind this pavilion are far from simple. Martin Roth, the former director of the V&A, co-curated the show, stating “Azerbaijan is a blueprint for the tolerant coexistence of people of different cultures.” But as many have been quick to point out, the oil-rich nation is ruled through corruption and brutality.

Still, the displays of bağlama and other musical instruments are lovely. And, although they may look a bit like Cornelia Parker’s work, these aren’t exploding, they are forming a global community.

The Pavilion of Humanity

Top Gun, Michal Cole

The grandly titled Pavilion of Humanity is actually a relatively small space, housing Objection, a collaborative show from Ekin Onat and Michal Cole.

There is a lot to like in this hard-hitting show.

Cole’s Top Gun is hugely impressive – she has sewn together thousands of neck-ties and lined a traditional male den, entirely wrapping the inside of the room in the material, even covering the trophy head on the wall. The work is reminiscent of Yinka Shonibare’s batik covered books (shown at Turner Contemporary) some of which is on display in the main space of the Giardini, and it’s just as powerful.

I also really liked her video piece, shown in a mocked-up bathroom. In Neverland she is dressed as a ‘housewife’, in gown and curlers, balanced in a gondola holding a mop, trying to soak up the waters of Venice. I liked it even more that someone has had to add a ‘do not use’ sign to the obviously not plumbed-in toilet in that room.

There is no lack of security here, Ekin Onat

Onat’s stand-out works are about security, particularly the security services. There is no lack of security here is a series of three pieces. My favourite (or maybe just the easiest to photograph) is this table setting, made from recycled batons and shields, affixed with fake security insignia.

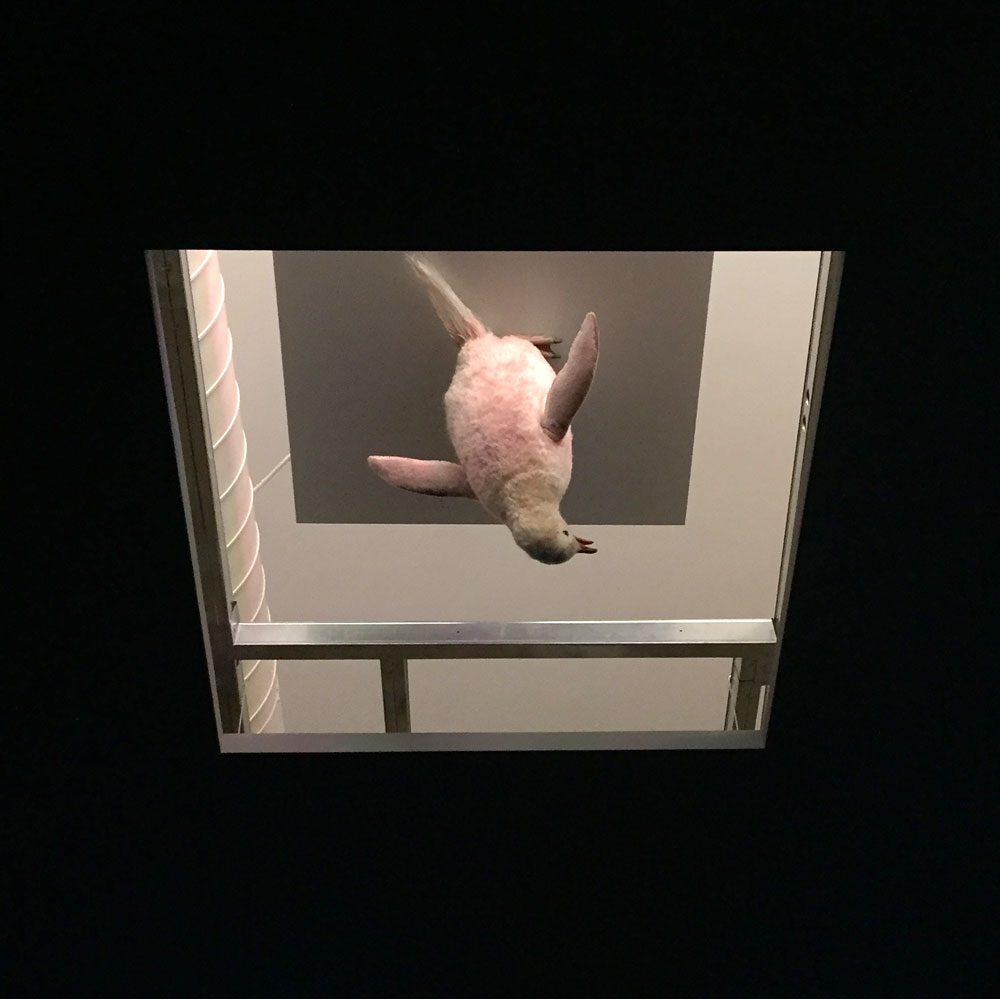

Pierre Huyghe

Creature, Pierre Huyge

Fondation Louis Vuitton is showing three works by Pierre Huyghe as their ‘Eventi Colaterali’.

The bizarre experience begins when you enter (through the back door, not the fancy shop-front) and have to wait for a lift that has little indication it is coming. For at least two minutes I thought that I was part of an experimental artwork. But eventually the door dinged and took me up three flights.

Displayed was Silent Score, where Huyghe got a computer program to transcribe the silence of a performance, of John Cage’s 4’33”, into a piece for flute. That feels a little like a fashion line inspired by the Emperor’s new clothes.

More impressive is the enigmatic film A Journey that wasn’t. This 21-minute film begins with a short narration explaining that they are on a mission to find something new, their only criteria is to not capture and bring it back. The film is then largely silent (save for ambient sounds) as an Antarctic expedition is intercut with some beautifully filmed audience shots at what looks like a kind of sea-life centre. Apparently Tate own the film so maybe it’ll be shown there sometime soon.

The third piece was hidden in the ceiling tiles. Creature was apparently created long before an albino penguin featured in the film.

And from the gallery you can walk out onto a balcony that overlooks the shop, and peer at the curiosities below.

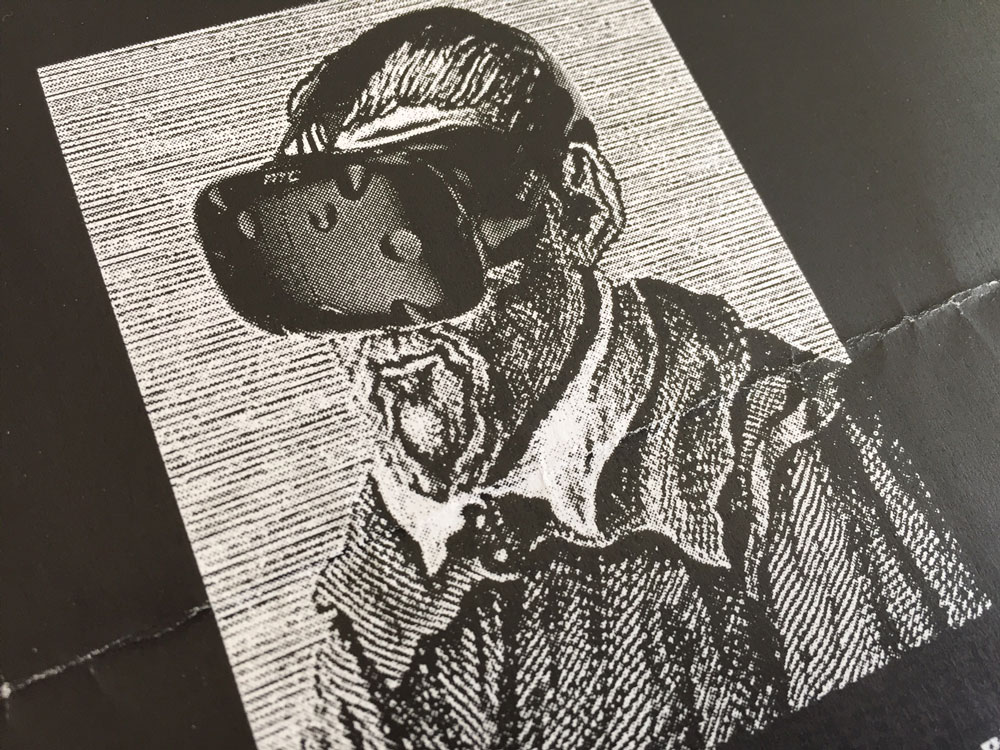

Ryder Ripps

Image from Diventare Schiavo, Ryder Ripps

Diventare Schiavo (Become A Slave) is a virtual reality experience by Ryder Ripps. There are two installations.

In the first, Virtual Reality Reality, you wear the full VR regalia and become a factory worker, boxing VR kits from a conveyor belt; all very meta as the simulation gets faster and faster until you are doomed to failure (or attain such mechanised actions that you disengage your brain).

In the second, Voice of God, a darkened room has one spot of light, an iPhone showing social media posts. Through quadrophonic speakers, different voices read the comments and replies to each post, underscored by Allegri’s Misere.

Mongolia Pavilion

Sculpture installation by Ch.Chimeddorj

The Mongolian pavilion carries the title Lost in Tngri (Lost in Heaven). It features five artists tackling subjects around human frailty.

It’s quite a small show that I might have walked straight past, but I was tempted in by a gaggle of intriguing flamingo-gun hybrids that mark the entrance and walk you into the space.

Glasstress

A grounded Twitter bird, Ai Weiwei

Glasstress is a commercial project. It costs €10 to get in and it’s worth every penny.

The space is packed with art, made from glass. Curator Adriano Berengo describes it as his “tribute and thank you to the island of Murano”.

Dustin Yellin

Amongst the standout pieces for me were the multi-layered works of Dustin Yellin. I made a video to show how they work.

Ai Weiwei had contributed a couple of pieces, including a vast chandelier, mostly created from his ubiquitous middle finger. And Jake and Dinos Chapman were in the mix.

But the most intriguing work was by Josepha Gasch-Muche who uses tiny slithers of glass to create texture that captures light like fur. Fragile, dangerous and complex.

T.30/12/07, Josepha Gasch-Muche

Talking of dangerous, I thought I was being very clever, spotting security glass on the window ledges, as I stared out at James Lee Byars’s 65 foot, The Golden Tower, across the canal.

Cotissi, Sarah Sze

But of course this was another art work. Sarah Sze’s Cotissi (Cotisso are chunks of Murano glass) runs all around the buildings window ledges.

The Stamp (Mquiaz), Abdulnasser Gharem

And the best is last… this stunning, oversized ink stamp, with an entirely smooth glass surface, that reads ‘In accordance with Sharia Law’ and would shatter if ever used.

It is one of many oversized stamps (most actual, working rubber stamps) that form the core of this artist’s wide array of conceptual work. He is also a lieutenant-colonel in Saudi Arabia’s army and went to school with two of the 9/11 attackers.

The ones that got away…

Finding the various exhibition spaces, around the city, is a bit of a hunt. And going in July feels a bit like you are outside of the normal hunting season.

The Biennale opens in May so that’s when the art world descends. By the scorching heat of July, interest has waned amongst the press and it seems amongst some of the exhibiting countries.

I searched in vain for the Welsh pavilion. The signs took me up a dead-end alley that was refuge to a number of homeless men. Perhaps it was an installation. I didn’t stay to find out.

Hybrid of Chrysler, Esterio Segura

Evoking the spirit of Cuba, this muscular Chrysler plane beckoned me across the piazza towards the Cuban pavilion. But the door was locked so I didn’t get to sample the The Perversion of Classics: The Anarchy of Narrations show.

Love My Hard Brexit. A shop display that might well be an art installation.

But the Cuban pavilion was directly opposite a fascinating ‘shop’, filled with neon, kitsch and outlandish fashion, amongst photographs of glamorous glory days and signed Andy Warhol posters. I repeatedly tried to get the attention of the woman behind the counter (to ask if I could take a photo of her no photography sign) but she totally blanked me. I still don’t know if this was a melancholic art work or an actual shop, frequented by wilted flower-children.

[Actually I’m now a little nearer knowing as I’ve done some more research. I was in the Fiorella Gallery.]

Wandering around that area, I also stumbled into the Iraq pavilion. Titled Archaic it contained some exquisite historical pieces, many leaving the National Museum for the first time since 1988 (and the post-invasion, televised looting of 2003).

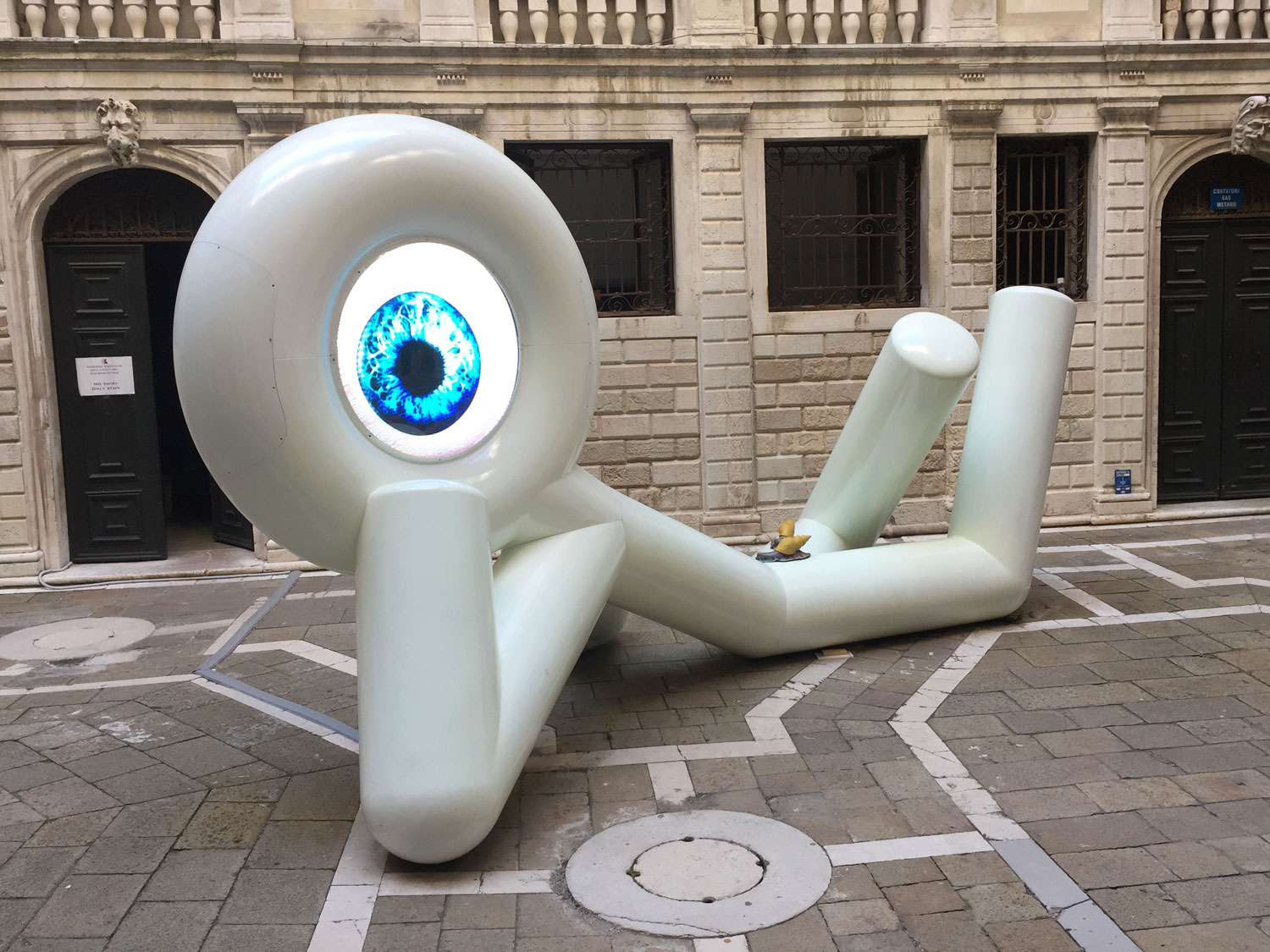

And that led to a courtyard advertising ‘Body and Soul, Performance Art – Past and Present‘. It was getting late and that was closed too. But my partner and I followed a small group of people into an open courtyard and discovered Lina Condes’s Extraterrestrial Odyssey amongst other smaller works.

Extraterrestrial Odyssey, Lina Condes

This anthropomorphic sculpture has a moving eyeball and (inexplicably) two golden snails on its bum. Apparently, it sets out to “create an expressive dialogue with the public, becoming a bridge between creativeness and technological research”.

It was good fun and when its eye turned to hearts and it blew a wolf-whistle, I knew it was time to call it a day and end my Venetian adventure. You can be sure I’ll be back in two years.