2017 saw the fourth Folkestone Triennial, nine weeks of art happenings, centred around commissions from some of the world’s best contemporary artists. Michael visited the seaside town to experience it.

Folkestone Triennial 2017

Ten years ago I took the very long train trek to Folkestone for a meeting with the team behind a new art initiative, an event that would happen every three years, to be called the Triennial.

It was a grim day. Searching for somewhere to eat, I trudged past the boarded-up shopfronts of the old town, down to a chip van in the car park of the vast, abandoned industry of the dockyard. Turning my back against the driving drizzle, I used my umbrella to fend off the seagulls.

It has taken me a decade to revisit, drawn by the promise of major works by big name artists at the 2017 Folkestone Triennial.

Sitting in the long shadow of Lubaina Himid’s Jelly Mould Pavilion, on the newly landscaped beach.

What I found there was a surprise, a revelation. Folkestone has been transformed with hipster cafes, gourmet restaurants and micro-brew-bars. The docks have been stripped out and rebuilt into a mini-pier for 21st century perambulation (past dozens of mini food stalls, as far as the Lighthouse Champagne Bar at the tip of the bay). And there’s now the 140mph Javelin train that delivers you from St Pancras in a little over an hour.

Perhaps my view was unusually rose-tinted by the glorious weather; a low autumn sun cast long shadows and illuminated the town with the Turneresque light that has helped to rejuvenate nearby Margate.

Folkestone was heaving with people, many following maps to the artistic treasures along the beach. I had tried to download the Folkestone Triennial app but, like so many such apps, it crashed and froze so often that I gave up and reverted to folded paper.

Let’s get my other moan out of the way too. This year’s Triennial seems to be titled ‘Double Edge’. I’ve no idea why, it really doesn’t (from an audience perspective) need an extra theme or title – it was just confusing to everyone I spoke to about it.

Moaning over, I had a great day, filled with interesting art. Here’s a run down of a few of my favourite pieces, starting at the west of the town and walking east. Some are this year’s commissions, some are still in place from previous Triennials…

David Shrigley’s Lamp Post (as remembered)

David Shrigley is currently one of the biggest names in contemporary British art. He’s leapt from the cartoon strips of the Guardian onto the Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square. For this commission he’s taken conceptualism even further – he doesn’t seem to have touched the work at all.

Shrigley asked his artist friend, Camille Biddell, to visit Folkestone and spend 40 seconds memorising the look of the iconic lamp posts along the seafront. She then returned to her Edinburgh studio to create her interpretation, from memory and sketches. Apparently, the work exemplifies the transition of the town from seasonal tourism to creative industries. Maybe. It is a fun experiment in memory and authenticity.

Mark Wallinger’s Folk Stones

Commissioned for the first Triennial, Mark Wallinger’s Folk Stones at first feels like a two-dimensional pun – individually numbered pebbles from the beach, set in concrete like those pieces of urban landscaping that discourage pedestrians around the town’s one-way system.

But these 19,240 stones have a deeper resonance. Each represents a British soldier killed on a single day, 1st July, at the battle of the Somme. They were amongst a million young men who would have left for the battlefields of the Great War, from the beaches of Folkestone.

Christian Boltanski’s The Whispers

Close to Wallinger’s Folk Stones is a collection of wooden benches, looking out to sea, facing mainland Europe. Each bench has a motion-triggered audio player. French artist Christian Boltanski encouraged local people to donate the letters of World War One servicemen (often written as they camped in Folkestone, preparing to leave for battle). He then commissioned those local people to read these poignant, everyday messages of love and longing.

It’s an intimate and upsetting piece. Commissioned in 2008, it’s remarkable that the technology is still active and still affecting to anyone who takes the time to sit and stare across to the battlefield of France and Belgium.

Ruth Ewan’s We Could Have Been Anything That We Wanted To Be

We’ve probably all mused about the possibility of decimal timekeeping, but I didn’t know the Republic of France had adopted the model in 1793. For her 2011 commission, Ruth Ewan demonstrated the idea by creating clocks of 10 hours, each hour divided into 10 minute divisions.

The piece is made more powerful because, from the vantage point of the cliff-side walk (where the work is sited), we can clearly see the beaches of France where Napoleon’s troops would have camped, preparing for a British invasion.

The title is a bit of a mystery though – I wonder why she’s used a song title from the children’s musical Bugsy Malone, ‘We Could Have Been Anything That We Wanted To Be’.

Richard Woods’s Holiday Home

Dotted throughout the town, and its surrounds, are six Holiday Homes, by sculptural artist Richard Woods. Each identical in size but painted a different garish colour, they are perfect pieces for this sort of commission. These are bold, playful artistic statements that allow different viewers to project their own meaning onto them. Woods seems happy for people to do just that.

Perhaps they talk to the issues of second-home owners in a town where housing is becoming increasingly unaffordable (ironically because of the kind of gentrification that is created by artist communities, and draws creative people to the flame).

Richard Woods’s Holiday Home

Maybe they suggest a kind of alien presence, refugees washed up on the shores of Kent, plonked into communities, struggling for acceptance.

Or they could just be a critique of the types of starter-homes that are available to young people in the area – cheap, cheerful and too small to be practically useful.

Richard Woods’s Holiday Home

Whatever the explanation, the houses are extremely photogenic and ideal fodder for social media. Their bright colours and thick black outlines make them look drawn onto the landscape. They become the ultimate – ‘that’s not art, my three year old could draw better than that’.

Antony Gormley’s Another Time XVIII 2013

After a trek along the beach, past the site of the large-scale Bill Woodrow piece that still hadn’t turned up (a month after it was supposed to be installed), Lubaina Himid’s fun Jelly Mould Pavilion (shown earlier in this entry), and A K Dolven, Out of Tune (a rejected church bell, suspended high between two posts, that I really wanted to ring), we reached the harbour arm cum pier.

Perched in the moss-coated wooden lattice, beneath the new walkways is one of Antony Gormley’s 100 casts of himself, titled Another Time. They were created to ‘bear witness’ to their surroundings, to signify the quiet contemplation of the space as it is affected by the natural elements that surround it.

It’s amazing to see the draw of Gormley’s work, with people (including me) queuing and scrapping to get the best Instagrammable snap. This figure doesn’t get a lot of time for solitude and introspection.

This is one of three loaned pieces, one is sited further along the coast (see below) and the other is in the tidal flow, outside Turner Contemporary in Margate.

Michael Craig-Martin’s Folkestone Lightbulb

Walking into the old town, it’s impossible to ignore Michael Craig-Martin’s brightly coloured mural. The Folkestone Lightbulb is a welcome addition to the facades but I can’t help thinking it’s going to look pretty tired, pretty quickly.

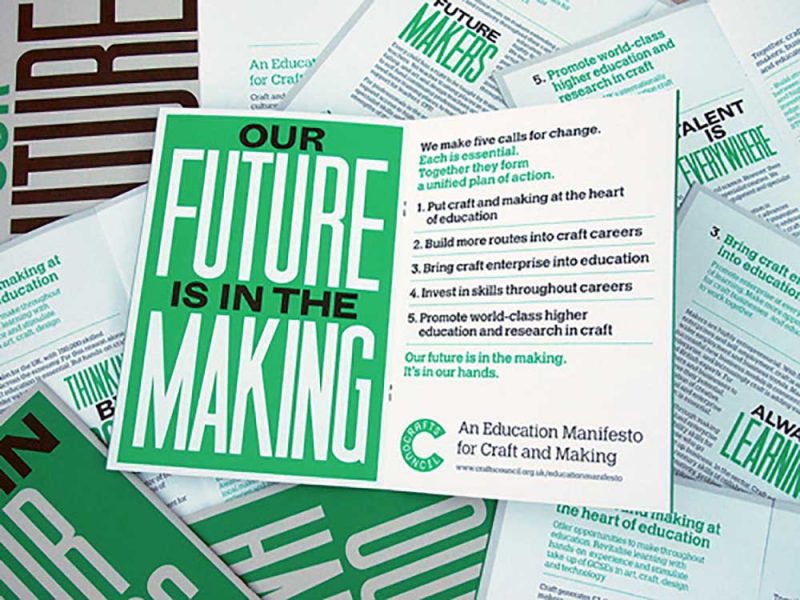

Provocations from Bob & Roberta Smith

In the shopfront below the lightbulb is the nerve centre of an all encompassing project from artist Bob & Roberta Smith. The town is filled with banners and graphics proclaiming that Folkestone is an Art School.

It’s a topic that Bob is passionate about and he’s set up dozens of classes in this shop to demonstrate his point. And there’s an accompanying multi-part video tutorial series on YouTube.

Bob’s ‘piece’ is truly immersive. He’s working with schoolchildren, teachers, local artists and anyone who happens to be passing by.

In the morning I was there, I assume he’d been working with children to make protest placards, as I spotted these children with their excellent slogans (I’ve no idea what the installation behind them is, it doesn’t seem to be part of the Triennial).

Children with their placards of ‘protest’

His work does what all great art should do, it makes you question your own thinking, he stops you in your tracks and reprogammes you so you never see the world in quite the same way again.

Jonathan Wright’s Fleet on Foot

In 1299, Folkestone was nominated a tributary ‘cinque port’ to Dover. At the time, the town had a fleet of just seven boats and a tidal inlet along the Pent Stream.

Now that stream is hidden beneath Tontine Street, so the artist Jonathan Wright has placed seven gilded boats (digitally printed replicas of current Folkestone-based boats) on poles along the street, beside them are plaques that detail their crew and markings.

Antony Gormley’s Another Time XXI 2013 (Coronation Parade)

Heading out of the town, along the seafront, it would be easy to miss the steps down to the Coronation Parade (a long series of archways, installed in the 1930s to shore up the cliffs above them), I’m pleased I didn’t.

Walking through the arches is fun enough but your extra reward for the journey (only possible at low tide) is to get up close and personal with another of Gormley’s casts.

Marc Schmitz and Dolgor Ser-Od’s Siren

Climbing up from the seafront onto the cliffs of the North Downs, you come across Siren, looking like an ear-horn for an ogre in a Dr Seuss story.

It evokes the feeling of the lo-fi concave concrete listening devices along the coasts (a theme picked up by Anish Kapur’s C-curve, on the South Downs), or the air-horns of now abandoned lighthouses.

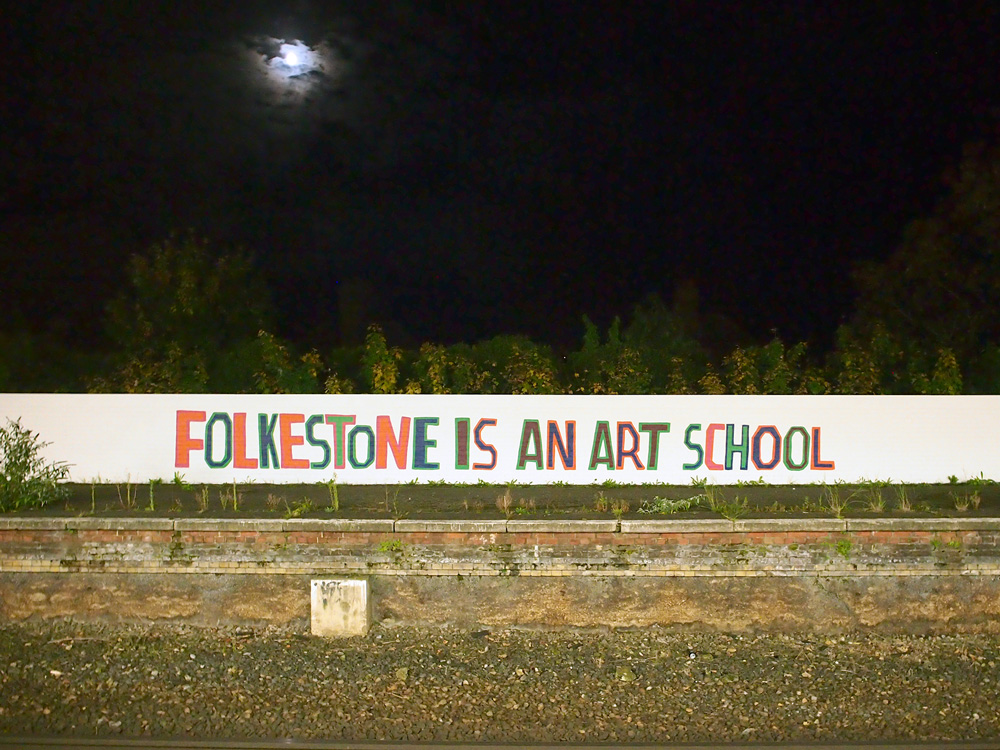

Part of Bob & Roberta Smith’s Folkestone is an Art School

At the top of the cliff is one of a series of Martello towers (cannon emplacements, built in the 19th Century, as part of Britain’s sea defences). Wrapped around it the enormous manifestation of Bob and Roberta Smith’s statement. It’s difficult to get a sense of scale but the barely visible red bi-plane, flying above it, gives a sense of just how huge the installation is.

Alex Hartley’s Wall

Further along the clifftop, my tour ended with perhaps my favourite installation of the 2017 Triennial. Wall is a complex piece. A cage, made from similar fencing to that used in the refugee camps in Calais, contains Iron Age millstones, found at this site. The Wall is balanced on steel girders, over-hanging the cliff edge. The weight of history counterbalancing the precarious structure that points across the channel.

Presumably, as the cliff continues its inevitable erosion, the querns will fall, one-by-one and the structure will eventually topple into the sea.

I can only imagine the health-and-safety meetings and insurance underwriting required to install this work, and allow the public so close to the edge of the cliff. Full marks to the Canterbury Archaeological Trust who commissioned it.

A long, fun, enlightening day in Folkestone ended back at the station where the moon shone almost as brightly as the sun had done, and I departed to one final reminder from Bob, that Folkestone really is an art school.